There’s no room for waste in public-sector investments of dollars and human capital. A Center for Results-Driven Governing has been established at the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) to increase confidence in outcomes by curating and sharing lessons learned from decades of evidence-based policymaking.

“The center isn't going to tell policymakers what they should do," says its director, Kristine Goodwin. "We're providing resources that will help them ask questions and identify solutions, and that won't look the same in every state.”

“This area is ripe for sharing what’s working,” she says. “NCSL can be effective by raising awareness among legislators and legislative staff about what evidence is and what questions can be asked and connecting states with one another.”

Doing More With Less

The center was formed with support from the Pew Charitable Trusts, and draws upon a decade of work by Pew’s Results First Initiative. It’s a good idea to make more resources available at this time, says Results First director Sara Dube.The Pew initiative originated on the heels of the Great Recession, she says, when it became clear that states needed data and evaluations to make the best-possible use of limited funds and to do more with less. Budget situations improved over time, but a commitment to evidence persisted.

The Results First Clearinghouse Database is a repository of information about more than 3,000 programs, rating their impact according to the findings of high-quality evidence. Such accumulated knowledge can help point the way out of the overwhelming downturn the pandemic has caused.

“Budgets have taken sharp declines in very dramatic ways, and in very, very short timeframes,” she says. “Legislators, executives and decision-makers are searching for ways to help them confront declining revenues and the skyrocketing needs of their communities.”

Pew and NCSL have collaborated for years, and Dube is a member of the working group that advised the formation of the center, along with state legislators, their staff and executive branch officials. As part of their formative work, the advisors developed a set of principles and strategies for state policymakers.

The NCSL center aims to provide more assistance to more states seeking to implement these approaches. It will add strength to the work that Pew and groups such as Results for America and the Center for Evidence-Based Policy are doing to advance the field, work with appeal that cuts across political boundaries.

“We’ve worked in blue states, red states, purple states, states with split houses and states with splits between the executive and the legislative branch,” says Dube. “We’ve seen interest in the use of evidence across the aisle and across the branches.”

Even if this is generally true, cross-branch support and collaboration are essential within a jurisdiction if evidence-based policymaking is to succeed. The Alabama Commission on the Evaluation of Services (ACES), created in 2019, was designed to facilitate such a culture.

A Cross-Branch, Cross-Party Conversation

ACES is comprised of members from the legislative and executive branches of Alabama state government, with representatives of both political parties. This arrangement benefits from lessons learned in states where one branch alone conducts program review and evaluation, with resulting potential for pushback or conflict over findings.Before ACES was formed, the Alabama Legislative Services Agency had worked with Results First to analyze results from more than 50 mental health programs. Early on, officials viewed the Legislature’s evaluations and reports as an attempt to control how they did things, says Marcus Morgan, the director of ACES. Forming the commission and bringing in the executive branch, and its expertise in the day-to-day workings of state government, has helped change the perception from oversight and overreach to partnership.

“By having voices and equal membership from both sides, you have the start of a conversation about how best to approach something,” he says. “It’s not from one side or the other, it’s a collaborative discussion.”

ACES is tasked with bringing a data-based lens to every program that receives a direct budget appropriation, including health and human services, education, criminal justice, and youth and rehab services. Morgan and his staff make an annual work plan for evaluations based on four principals -- efficiency, effectiveness, collaboration and capacity -- though all four may not apply in every case. Collaboration, for example, can be a significant factor if multiple agencies are working to accomplish the same outcome, with potential for redundancies.

Identifying and collecting the right data elements for evaluations is an ongoing challenge, says Morgan, one that involves multiple sources, scrubbing agency data to make it useable and background worries that useful data exists in places unknown to evaluators. A recent prison education and recidivism evaluation involved meshing data sets from numerous systems.

“We’ve learned from working with other jurisdictions that we all struggle to find the right data to use in evaluation,” says Morgan. “Where there are gaps, you have to find the right way to tell the story.”

ACES officially became an organization in fiscal year 2020. In its first year, it has focused on building relationships with agencies and convincing them that its role is not to advocate for either cuts or expansion, but to present facts that can help solve problems.

Morgan is hopeful that the commission’s attention to inclusiveness will help it survive multiple administrations and give it time to grow interest and support through reports, public hearings and re-evaluation of programs after changes have been made. “We’ll see if that’s going to work,” he says.

Risk, Data and Fidelity

There’s no place to hide when investments in community safety fail to achieve the desired outcome. Crime and recidivism are visible and measurable. Beth Skinner, Ph.D., the director of the Iowa Department of Corrections, has spent much of the past two decades developing an understanding of the ways that evidence-based practices can give meaning to the word “correction,” to the benefit of offenders and citizens alike.Before assuming her current post two years ago, she managed programs for the Sixth Judicial District in Cedar Rapids that ranged from housing, reentry, workforce development to parole and victim services. She directed reentry efforts within the National Initiatives Division of the CSG Justice Center, a position that gave her the opportunity to talk to prison officials throughout the country about their experience implementing evidence-based programs. Skinner then returned to Iowa to coordinate a statewide recidivism project funded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance.

“To do public safety correctly, and to get the best outcomes, you need data,” she says. “The data tells us where we need to invest resources.” The department’s system for managing offenders includes a dashboard that is accessible to staff at all levels, from case managers, supervisors and wardens to Skinner.

An inventory of the programs offered to inmates at all nine of the state’s prisons rooted out any that were not evidence-based and reallocated staff to four core programs. Skinner also discovered that 60 percent of those who were incarcerated were leaving without participating in any programs that could help them address the behavior and life problems that landed them in prison. “We recognized through the data where we need to build more capacity for post-secondary education, apprenticeship and vocal rehabilitation programs,” she says.

“In evidence-based practice, you need to make sure that your tools are being used with fidelity, properly and as designed,” she says. “We continue to do audits of our risk assessment across the state to ensure that people are using the instrument correctly, which means that we’re targeting programs and case management to the right people.”

The department also reviews demographics from its prisons and community-based programs. If racial disparities exist regarding things such as access to programs and job assignments or parole revocation, the prison or district involved must report this and develop a plan to address what was found.

Shifting to an evidence-based culture includes making sure that staff and community partners understand why and how the programs they are being asked to implement work, says Skinner. “There’s no silver bullet; there have to be lots of things in place to really reduce recidivism.”

An Evidence Continuum

Budget constraints caused by the pandemic mean that programs may face cuts even if they are achieving measurable results. Colorado, long recognized for evidence-based policy leadership, has developed an approach to the budget process that has special relevance at this time.Gov. Polis has built on work of his predecessor to increase the use of data and evidence in budget decisions, says Aaron Ray, deputy director for education, workforce and environment in the Governor’s Office of State Planning and Budgeting.

“We started with a few policy areas that were ripe for this kind of work, and we've now expanded to applying that same approach to the entire budget,” says Ray. “There’s lots of nuance about what that means for a specific budget line, and it’s our day-to-day work to figure that out.”

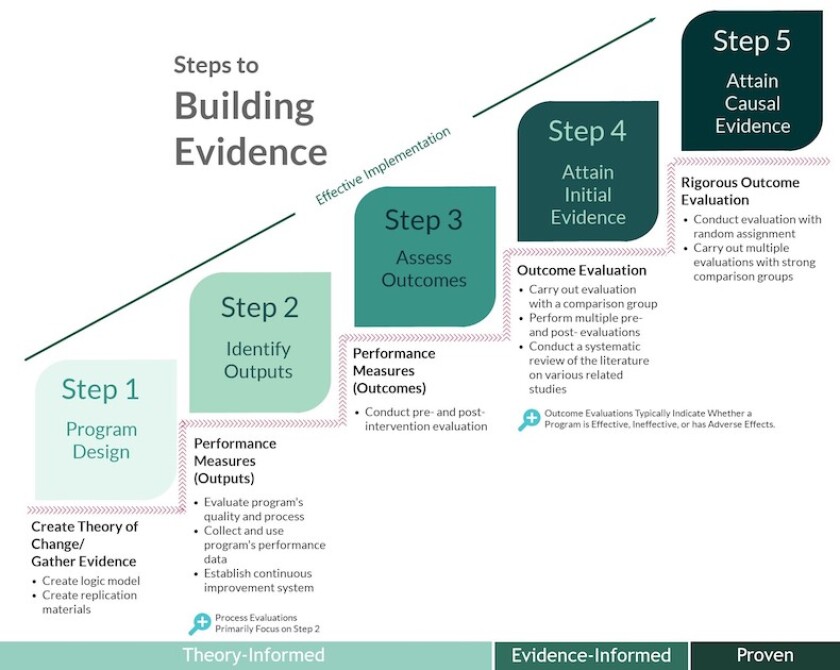

Opinions vary about exactly what the term “evidence-based policy” means, he says. To guide its efforts, Colorado has developed a five-step evidence continuum that outlines the types of supporting evidence that help programs move from “theory-informed” to “proven.”

Ray, who holds a Ph.D. in political science, an MPP in environmental and regulatory policy and an M.A. in education, is well-equipped to judge where programs stand on this continuum. Randomized controlled trials are the gold standard, he says. Some programs have been subjected to them, but for a variety of reasons they’re not always possible.

Documents outlining budget requests now include an “evidence meter” whenever possible, showing where a program sits on the evidence continuum. A third of the requests in the November governance budget were accompanied by the meter. On average, the programs where funding increases were requested were higher on the scale.

“For those that we requested decreases, it was related to having less information about how effective the program was,” says Ray. “We think that’s how the system should work.”

Moving Beyond Belief

Along with Aaron Ray, Beth Skinner and Pew’s Sara Dube, Colorado Senator Chris Hansen is a member of the NCSL work group that helped define the work of the Center for Results-Driven Governing. He’s convinced that its work is exceptionally important at this time.“We’ve had an erosion of the public trust in government, in facts,” he says. “I can’t think of a worse situation to be in, when we have the two parties essentially talking past each other.”

Colorado’s emphasis on evidence has helped insulate it from some of the worst impulses that have emerged nationally, he believes. There are goals that both parties share, and agreement is best built on a foundation of evidence.

Reducing recidivism is a shared goal, for example, and the state has had success with evidence-based approaches to youth corrections. Following on research in Missouri that showed that creating a home-like environment for youth offenders led to better outcomes and fewer repeat offenses, Colorado invested in couches, curtains and other home-like fixtures.

Hansen, who has a Ph.D. in energy and economics, shares Aaron Ray’s appreciation for scientific rigor. One goal for the coming year, he says, is to get definitions and standards in statutes, so that all parties are measuring claims with the same barometer.

It’s deeply disturbing that large numbers of citizens, right- and left-leaning, are amenable to conspiracy theories or able to be convinced that the earth is flat, he says. Using evidence to make policy, and communicating about it to the public, can be one way to overcome this.

“It's so important that we communicate scientific concepts and get rid of that word ‘belief,’” says Hansen. “That is a word for Sunday morning, and it’s not applicable to what we're trying to do with science-based policy.”