(Photographs by David Kidd)

Almost immediately, the four girls came to symbolize a turning point in the civil rights movement. “They are the martyred heroines of a holy crusade for freedom and human dignity,” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said three days later, before 3,000 mourners.

Barely mentioned in newspaper accounts of the day, there was a fifth girl in the church basement the morning of the blast. Addie Mae Collins’ younger sister, Sarah, was the last person to see the girls alive. Just a few feet from her friends, 12-year-old Sarah was bloodied, but still standing, in a cloud of dust and rubble when a rescuer scooped her up and took her outside through the gaping hole created by the bomb.

Sarah Collins was not able to attend her sister’s funeral. She would never meet Dr. King or hear him eulogize Addie Mae and their friends. Instead, she would spend months in a hospital bed, her face and chest disfigured from flying debris and shards of glass. Doctors could not save her right eye. Long a footnote to history, Sarah’s story is largely unknown or forgotten by most everyone familiar with the story of “the four little girls.” But she is alive.

With no help from the city of Birmingham or the state of Alabama, Sarah continues to be responsible for a lifetime of medical expenses related to her injuries. “I haven’t got restitution,” she says. “And yet I’ve still got to pay the bills when I go to the doctor.” After all these years Sarah is still determined to get her due. And she is no longer fighting alone.

From Birmingham to Bombingham

An entrenched system of segregation persisted well into 20th-century Birmingham. Better-paying jobs were off-limits to African Americans who were corralled into their own distinct neighborhoods. But by the late 1940s, the color line began to be tested as middle-class black families moved into white neighborhoods. The backlash was at times intense.

Neglected and crumbling, the giant “Magic City” sign was torn down in 1952. By then the city had come to be known by a new name, “Bombingham,” due to the number of racially motivated attacks on black-owned homes, churches and meeting places. Beginning in 1947 and through the nearly two decades that followed, there were more than 50 unsolved bombings and assaults. One neighborhood is still known as Dynamite Hill because of the number of blasts that occurred there.

A Segregated City

Segregation was not just the custom in Birmingham, it was the law. The city passed a number of ordinances between 1944 and 1951 that were intended to enforce the strict separation of races and maintain white supremacy. Restaurants were prohibited from serving whites and blacks in the same room. Streetcars had to provide separate entrances and exits. Even pastimes did not escape regulation. “It shall be unlawful,” one statute decreed, “for a Negro and a white person to play together or in company with each other in any game of cards, dice, dominoes, checkers, baseball, softball, football, basketball or similar games.”

(Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group. Photo by Lewis Arnold, Birmingham News)

Martin Luther King Jr. and members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference joined forces with Shuttlesworth, initiating a series of sit-ins and marches, intended to provoke mass arrests. King, among the hundreds arrested, wrote his seminal “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” from a prison filled to capacity.

As part of the spring offensive, hundreds of school-age youth were encouraged to march through the downtown streets as part of a “Children’s Crusade,” departing in groups of 50 from the 16th Street Baptist Church. One such student demonstration was met with police attack dogs and high-pressure fire hoses, under the direction of Eugene “Bull” Connor, the city’s commissioner of public safety. Film and photographs of the confrontation provoked national outrage, galvanizing widespread support for civil rights reform.

(Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group. Unknown photographer, Birmingham News)

Sept. 15, 1963

Sarah Collins and her older sisters, Addie Mae and Janie, set off for church on foot Sunday morning, the 15th of September, 1963. The sky was overcast, with temperatures in the mid-60s. It was a mile and a half between their small wood frame house and the 16th Street Baptist Church. “That Sunday we were going to have a youth day program,” says Sarah. “And we were so excited.”

Janie was carrying a purse that looked like a little black football. In a playful mood, the sisters made a game of it, throwing the purse back and forth among themselves as they made their way to 16th Street. “We [were] just runnin’ and catchin’ it,” Sarah says. “We were laughing all the way.” Whether or not their impromptu game of football was the cause, the walk took longer than usual, and the girls arrived late to church.

With Sunday school already in session, the three sisters headed instead to the ladies’ lounge, tucked into a back corner of the church basement, not far from where Addie Mae and Sarah’s class was meeting. After a few minutes, Janie left the lounge and headed to her class upstairs, admonishing her sisters on her way out. “Y’all hurry up and go on to class, okay?” But rather than risk the wrath of their teacher for being tardy, the girls decided to stay where they were. Alone in the small lounge, they took a seat on the couch beneath a basement window and waited for class to be over.

(Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group. Photo by Tom Self, Birmingham News)

Before long, the four friends were together again, lined up in close formation, in front of the window. The windowsill was a few feet from the restroom floor, but level with the sidewalk outside. Sarah was standing at the sink, watching as Denise turned around and asked Addie Mae for help with her dress. “Addie, would you tie my sash,” she said. “And we all just stood there,” says Sarah. “Looking at Addie as she began to tie the sash.”

In the next instant, the ladies lounge was filled with a deafening roar and a maelstrom of flying dust, dirt, bricks and glass. The massive building shook on its foundation, nearly every window blown from its frame. Somehow still standing, with arms outstretched and blinded by the blast, Sarah called out for her sister. “Addie! Addie! Addie!” But there was no answer.

(Alabama Department of Archives and History. Donated by Alabama Media Group. Photo by Roy T. Carter, Birmingham News)

Home and Away

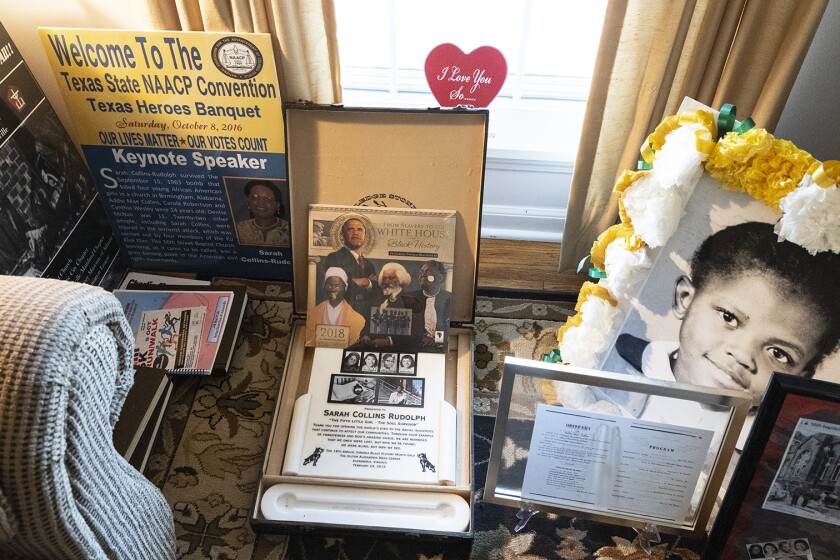

Seventy-one-year-old Sarah Collins Rudolph still lives in Birmingham, in a one-story brick house she shares with her husband, George. The white walls of their living room are covered from floor to ceiling with framed photographs, newspaper clippings, proclamations, citations and awards. Pictures of her sister Addie Mae, stuffed animals and candles share small tabletops with family photos. Larger pictures and awards are on the floor, propped up against the furniture and along the walls. “She’s got a lot of stuff,” says George, looking around the room.

Impeccably dressed in shades of turquoise and blue, Sarah has settled into a brown sofa at one end of the room. Sitting close, George provides a counterpoint in his grey Crimson Tide t-shirt and ever-present “Vietnam Veteran” ball cap. On this day in January, the tragedy of 1963 is once again on everyone’s mind in Birmingham. The last surviving parent of the four murdered girls will be buried tomorrow. George makes plans to drop off a condolence card to her family.

Sarah has struggled since childhood with the physical and emotional trauma suffered at the hands of the Klan bombers. Never has she received any help, financial or otherwise. “We didn’t have any counseling back then,” she says. Her childhood aspiration to be a nurse ended that day in church. More than 20 pieces of glass were removed from Sarah’s face, eyes and chest during her two-month hospital stay. There is still a shard of glass in her abdomen and another piece lodged in her one eye. Her doctor is afraid to remove it for fear of making her blind.

Having worked for years grinding pans in a foundry, she supports herself at age 71 as a domestic worker. “That’s not fair,” says George. “What happened to Sarah, other people did that to her. But she (ends up paying) for it.”

Most of the recognition Sarah gets comes from places far from home, as evidenced by the honors and awards covering her living room wall. George points to a stack of glossy photos of the two of them standing with President Biden in the Oval Office, a souvenir of a recent trip to Washington. “She’s been all over,” says George. “But Sarah has not got the recognition here in Birmingham that she really deserves. We’re sad that the city of Birmingham has not done enough for Sarah.”

Legal Help at Last

It was on one of Sarah’s trips out of state that she met Tom Bolling, a Washington, D.C., lawyer, traveling with his daughter on a civil rights tour through the South. Captivated by Sarah’s story, he was compelled to offer help in her search for restitution, enlisting his firm, Jenner & Block, in the cause. Recently retired, Bolling maintains an interest in Sarah’s case, as law partner Ishan Bhabha and others at the firm have taken the lead on seeking restitution for Sarah, pro bono.

In a September 2020 letter to Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey, Bhabha draws a direct line between former governor George Wallace and the church bombing. Sarah’s injuries “… were caused by criminals directly incited by state leaders to ‘take the offensive’ on white supremacy,” he wrote. “The actions of the bombers, affiliated with the Ku Klux Klan and inspired and motivated by then-Governor Wallace’s racist rhetoric, left Ms. Collins Rudolph hospitalized for months and scarred, both physically and mentally, to this day.”

Nine months before the bombing, in his inaugural address from the steps of the state capitol, Wallace famously declared his unequivocal support for “Segregation now. Segregation tomorrow. Segregation forever!” Just 10 days before the girls were murdered, the governor insisted that “What this country needs, is a few first-class funerals, and some political funerals, too.”

In his letter to the governor, Ishan Bhabha states that Sarah’s story “presents an especially meritorious and unique opportunity for the State of Alabama to right the wrongs that its past leaders encouraged and incited.”

“He provoked all this,” Sarah Collins Rudolph says of George Wallace, who died in 1998. “He provoked [all of] the racism.”

A Good First Step

Gov. Ivey responded to Ishan Bhabha’s letter within days. “… Many would question whether the State can be held legally responsible for what happened at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church so long ago,” she wrote. “Having said that, there should be no question that the racist, segregationist rhetoric used by some of our leaders during the time was wrong. …”

Her letter goes on to say: “There should be no question that Ms. Collins Rudolph and the families of those who perished … suffered an egregious injustice that has yielded untold pain and suffering over the ensuing decades. For that, they most certainly deserve a sincere, heartfelt apology — an apology that I extend today without hesitation or reservation.”

“It’s easy to kind of make her into this gauzy civil rights hero who you feel sorry for, and are inspired by, as opposed to somebody who has bills to pay,” says Bhabha.

“Sarah is being remembered in various ways because I think we’re revisiting the pain, the terrible pain of the past as a country,” says attorney Tom Bolling. “I think it’s tough for governments because of what restitution would really mean. It’s a very, very important public policy issue about doing justice and not forgetting. I suspect that forgetting is the easiest thing to do. But it’s not the right thing to do.”