This irreplaceable global market shut down as the result of abuse. Too much of the material it received was contaminated – not only could it not be processed and used to make new products, it created an unwelcome waste stream.

The impact on recycling in the U.S. was immediate, with a range of consequences. Some collection programs stopped altogether, others tightened the list of materials they would accept. Some sent recyclables to landfills or incinerated them.

This domestic crisis made it impossible to ignore weaknesses in recycling infrastructure that were well known within the industry, says Kate Bailey, the policy and research director for Eco-Cycle. A nonprofit, Eco-Cycle has provided recycling services to Boulder County, Colo., for 45 years, offering one of the country’s first curbside programs.

“We knew China was coming,” she says. “Everyone knew the bubble was going to burst; the silver lining in the National Sword policy is that it brought the challenges facing recycling to light and we’re starting to have some of the hard conversations that we should have had all along.”

The U.S. EPA has collected data about recycling rates. The numbers reflect the amount of material that has been collected for recycling, not an exact accounting of how much of this material has been made into new products.

What’s in a Word?

China’s policy shift shone a light on the fact that words such as “recycling” or “recyclable” had long been applied to aspirations as well as to reality. State and local governments didn’t track how much of the material they sent to China couldn’t be used. According to a 2020 report from Greenpeace, millions of tons may have gone to landfills and incinerators.

A California bill addresses another recycling complexity, the fact that manufacturers routinely place recycling symbols on plastics that are theoretically recyclable, but involve real-world challenges that make it unlikely they really will be reused. (According to EPA data, fewer than 9 percent of plastics in the waste stream are recycled.) If the bill passes, plastic products will only be allowed to use the“chasing arrows” symbol if they are made of material that is regularly collected, sorted, processed and used in new products.

Considering the countless entry points through which recyclable materials enter and leave the domestic waste stream, it’s not surprising that precise data about what happens to them is not available. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) collects and publishes data on recycling rates for a variety of materials. However, this data can’t be understood to reflect the rate at which these materials are made into new products – “recycled,” as most would understand the word. They show rates of collection, but exactly how much of the material that is collected finds new life is unknown.

Communities needed money to fill the recycling capacity void China had created, but the market dynamic didn’t help. The price for recyclables had crashed.

“The value of these commodities in the marketplace actually acts as a funding mechanism for recycling,” says Joseph Fulco, vice president of Casella Waste Systems. “It’s what makes the business work, what makes the public policy work. China disrupted the market even if you weren’t exporting recyclables there.”

Prices have been going up since 2018, but legislators in an increasing number of states are turning toward a policy solution that has been in place for decades in other countries to fund a more robust and effective recycling infrastructure.

Extended Producer Responsibility Laws

Making the Polluter Pay

Nearly 50 years ago, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development adopted the Polluter Pays Principle, meaning that a polluter should bear the costs of “measures decided by public authorities to ensure that the environment is in an acceptable state.” The concept of “Extended Producer Responsibility” (EPR), based on this principle, establishes that producers bear responsibility for the environmental costs associated with a product, throughout its life cycle.

Governments around the world, including state legislatures in the U.S., have enacted EPR systems for a range of products with environmental impacts. Packaging waste, including plastics, accounts for a significant portion of the waste stream (about 30 percent in the U.S.), and beginning in the 1990s, EPR laws aimed specifically at packaging began to emerge in Europe.

Today, these programs are in place throughout the European Union and in five Canadian provinces, as well as in Australia, Africa and South America. The mechanics vary, but the basic concept is that companies that sell products pay fees that help cover the cost of recycling packaging, shifting burden from taxpayers and government to those who are sending these materials onto the market.

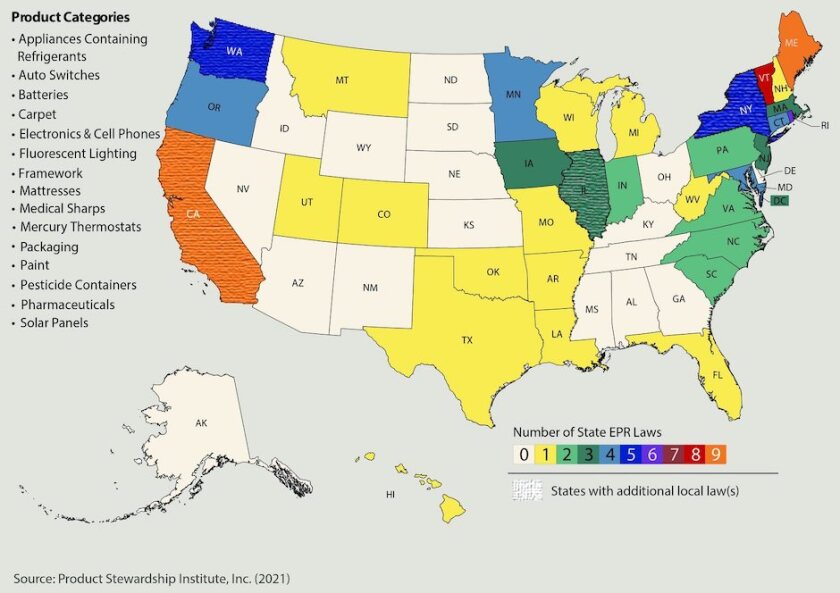

Over the past 20 years, the nonprofit Product Stewardship Institute (PSI) has helped 33 states pass 124 EPR laws, says its founder and CEO, Scott Cassel. Sixty EPR bills were introduced in the past year, he says, but the ones that excite him the most have to do with packaging.

Recycling rates have stagnated over the past two decades as the amount of packaging, the complexity of materials and costs have all increased. National Sword “exposed the system underneath that we all knew was not working,” he says, and fueled political will to require companies to help improve recycling. National and international outcry over gigantic ocean islands formed by microplastic garbage added to the urgency.

“Governments have no idea how to manage this stuff,” says Scott. “These systems give municipalities greater control over what is right now an open tap of products just poured into the waste stream.”

So far, legislators in seven states have responded to cries for help from local government by introducing EPR for packaging legislation.

On July 12, Maine became the first state in the nation to enact such a law.

(James F. McCarty/TNS)

In Line With the Developed World

“We were the first in the nation to do this, but we’re really just falling in the line with the rest of the world,” says Sarah Nichols, Sustainable Maine director for the Natural Resources Council of Maine (NRCM). “Most of the other developed countries already have a policy where producers are paying for the recycling of their packaging.”

“Somebody has to pay for disposal and recycling,” she says. “It’s more fair that it’s the cost causers and not the property taxpayers.”

In an EPR system, companies that sell products in the jurisdiction in question are required to be members of a stewardship organization that collects fees from them based on criteria, such as the amount of material in their packaging, the nature of it and the costs involved in recycling it. Fees are paid by companies selling products, the “brands,” not the companies that manufacture packaging. A company that is not a member of the organization can’t sell its products in the jurisdiction.

An organization of this sort does not already exist in the U.S., and so the Maine Department of Environmental Protection will put out an RFP to select it – but not before rule-making is complete regarding other details of its program. “It will be at least a few years before payments are made here and things happen,” says Nichols.

In addition to helping municipalities improve their recycling programs, funds collected from companies will enable investments in education about recycling and increasing access to recycling programs. Property taxes being used to cover recycling costs will become available for other uses.

There’s a focus on reuse as well, says Nichols. A producer that has a program to take back or refill their own packaging won’t pay a fee. “They only have to pay for the things that end up in the waste stream.”

Oregon’s waste stream was one of the first to be impacted by National Sword. In August, it became the second state with an EPR for packaging law.

A Question of Life Cycle

The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) approaches materials management from a life cycle perspective, says Sanne Stientra, DEQ project manager for the Recycling Modernization Act. “That involves emphasizing waste reduction and prevention, or things like reuse because they tend to have a much greater benefit for the environment than recycling, composting or other means of recovering materials.”

Every city and county in Oregon has its own recycling program, says Stientra, accepting different materials, charging different rates, using different service providers. Following National Sword, some dropped materials from their collection list. Some raised rates, charging more for less recycling.

(Eco-Cycle)

The bill that resulted reflects a “design for environment” approach as opposed to a “design for recyclability” approach, she says. “It may be better to make a product recyclable, or it may be better to do other things, like reduce the product/package ratio or use more post-consumer recycled content.”

The products included in the Oregon program, scheduled to be implemented in 2025, include packaging, food service ware and printed paper products such as magazines, newspapers and phone books. Companies must be a member of the Producer Responsibility Organization (PRO). Other measures in the bill include the creation of a list that will standardize collection of recyclable items throughout the state and a permitting process for processing facilities.

As in Maine, some of the money collected from companies will fund education and outreach to help reduce contamination caused by recycling customers. This includes the possibility of feedback from local government about their habits.

The fee structure was designed to respond to market changes, says Stienstra. “One of the big motivations was to take the burden of absorbing market volatility off the shoulders of rate payers and local government.”

EPR for packaging has found a foothold in the U.S., and multinational companies may already be familiar with such systems. But Sarah Nichols recalls “fierce” opposition to the Maine bill from brands, and companies that provide processing services have their own concerns.

Opportunity and Crisis

Victor Bell is U.S. managing director at Lorax EPI, a software company whose products include a tool that companies can use to calculate fees and fill out forms for any EPR program in the world. He has decades of experience working with companies participating in EPR for packaging programs in places as far flung as Europe, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Russia.

“A lot of the companies that have to pay fees are nervous about there being programs that are all different,” he says. Multinationals have been participating in EPR for a long time and may not be surprised to see it take root in the U.S., he says, but large retailers who sell products under their own brands that are made by others could be less prepared for it.

“Companies have been fighting this for years,” says Bell. Haulers and the solid waste industry worry that a PRO might be given responsibility for negotiating contracts with them rather than a city or town, or be empowered to suggest changes in their operations based on its perception of need.

Éco Entreprises Québec (EEQ) is a private nonprofit that has served as the stewardship organization for companies participating in the EPR for packaging program in Québec since it was established. The system has been working, says Mathieu Guillemette, senior director for EEQ. When China roiled the markets, municipalities did not have to shut down their programs because they knew they would be reimbursed.

A significant change is coming, however. In addition to collecting money from companies and distributing it to municipalities, EEQ will be responsible for managing the collection and recycling system and for selling material to recyclers, with targets for both recovery and recycling.

The 2018 crisis was a factor in this evolution. About half the material collected in Québec had been going abroad. “When the material went abroad, we lost track of what happened with it,” says Guillemette. As the full story of National Sword came to light, it became clear that it was not all being recycled. “As they say, never lose an opportunity, and the crisis was an opportunity to improve our system.”

Breaking Free

The Maine and Oregon EPR for packaging bills are landmark accomplishments. If they are followed by the success of similar bills in New York and California, the size of those markets could prompt packaging reform no matter how many other bills followed. A federal bill, the Break Free from Plastic Pollution Act, could bring EPR to every state.

The potential for such programs is well established. According to a report from the Extended Producer Responsibility Alliance, EPR has helped 10 of its EU members achieve recycling and recovery rates of 70 percent or more, with several attaining rates as high as 90 percent. In 2020, the stewardship group for British Columbia's EPR for packaging program, Recycle BC, reported a 52 percent recovery rate for plastic, exceeding its 2025 target. BC achieved an overall recovery rate of 85.8 percent, up from 77.4 percent the year before despite the fact that the program cost per metric ton increased. The quantity of post-consumer plastic packaging waste sent to recycling increased 92 percent in the EU between 2006 and 2018, reaching an overall rate of 42 percent.

The benefits go well beyond recovering and reusing recyclables at a higher rate. EPR has inspired innovations in package design, from increased use of recycled material to the simplicity of cutting back on weight or packaging elements. (For example, European brands have eliminated the boxes that surround toothpaste tubes.)

Plastic, the least recycled material, is ubiquitous in packaging and a prime target for EPR. Packaging reform around plastics can include strategies such as bans on single-use products, recycled content mandates, deposits for plastic bottles and reuse and refill policies.

Reducing plastic pollution is an environmental health priority, says Yinka Bode-George, environmental health manager for the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators. “Even before it hits our waterways, plastic has detrimental effects on our communities,” she says. “The way we talk about waste and plastic pollution is centered around ecological systems — the zero-waste movement hasn’t done a good enough job articulating the health impacts.”

Company support to improve processing will do much more than reduce packaging waste, says PSI’s Scott Cassel. “Many of our recycling mills, paper mills and plants for glass and plastics shut down because all the material was going to China — we're going to see more of a thriving, domestic recycling industry, creating jobs and economic development here.”

“It's going to make a new set of clothes for all of us that is much better than the ratty ones that we've been struggling with over the past 15 years.”