(David Kidd/Governing)

At the time, three shifts of miners were moving up and down Morris Drive every day, along with a hundred or more coal trucks trailing clouds of black dust behind. “The water was pretty good at the time,” remembers Eddy. But two centuries of mining in the nearby mountains has taken its toll.

Twenty years ago, the two neighbors decided that something needed to be done to reverse the environmental damage caused by polluted runoff seeping from nearby abandoned mines. Together, they formed the Morris Creek Watershed Association (MCWA), a nonprofit community organization dedicated to restoring the creek. “The stream was dead of aquatic life for about 30 years,” says Eddy. “About 2000, Mike was prodding me to do something to clean this up. To take care of the creek.”

Careers in Energy

Mike and Eddy have no direct connection to coal, but both spent their lives in the energy field. “In my career with the power company, there’s probably not a hollow or a tree or anything else that I don’t know about,” says Mike. Retired now, he continues to operate a school for prospective linemen down the street from his house.

Enjoyment of the outdoors and an appreciation of the area’s rugged beauty made settling here a natural choice for both men. But there was work to be done if their little community by the creek would thrive, or even just survive.

A Legacy of Pollution

AMD occurs when water flows over and through abandoned mine refuse, dissolving iron, manganese and other minerals. This metal-rich water ends up in streams and rivers, killing aquatic life, threatening drinking water and discouraging recreational use. Nearly 2,000 miles of streams and rivers in the coal mining regions of West Virginia are negatively affected by acid mine drainage. Nationally, more than 12,000 miles of waterways are degraded by AMD, nearly all of it originating from abandoned mines.

Cleaning Up

Officially operating since 2003, one of MCWA’s first tasks was to identify four primary project sites where the effects of acid mine drainage could be mitigated.

With grants and assistance from state agencies, a team of volunteers from MCWA set about building four AMD passive treatment facilities and stabilizing the stream banks. All together, more than 2,000 trees have been planted, including hundreds of blight-resistant native American chestnuts. Trash and debris was also a big problem in Morris Creek.

Life Returns to the Creek

Soon, life began returning to the stream. “We started getting the biological critters back in the streambed,” says Eddy. “All kinds of little things that live in the sand and gravel in the streambed. Once that was restored, we had a food supply that could then support crawdads and minnows and salamanders and all that good stuff.” Once they had something to eat, brown trout were released into the creek. When they did well, rainbow and brook trout were also introduced. “After being dead for 30 years, today we have a stream that supports three species of trout,” says Eddy. “It’s the only stream in southern West Virginia that can make that claim.”

Treating Acid Mine Drainage

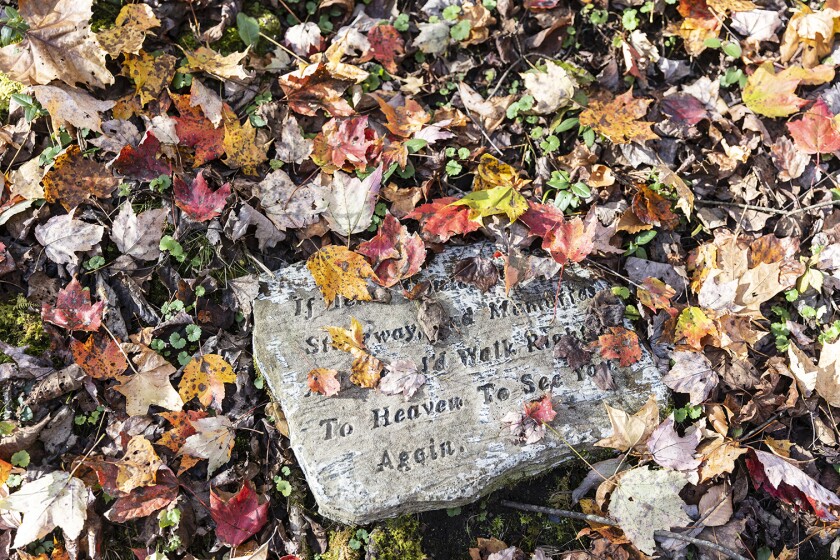

It’s a sunny but cool November afternoon and Eddy Grey is making the 20-minute walk from his house to the farthest of the four AMD mitigation sites. Known as a limestone contact treatment facility, the site consists of a series of stepped holding ponds at the base of a steep hill, dense with brush and trees. Pale brown and red leaves are scattered over the surface of the first and highest pond. Bright orange and yellow leaves line its shallow bottom. A long thin pipe slopes down the hill, bringing acidic water from a sealed mine portal. Its open end hovers over the pond.

The process of treating this polluted water is relatively simple. “It’s nothing more than for water to come through and come in contact with limestone,” says Eddy. As it enters the first pond, the mine drainage is acidic, so it has a low pH. As it flows over and through a series of limestone step dams, contact with the limestone causes the pH level of the AMD to be raised, which causes the dissolved iron, manganese and other heavy metals to drop out as solids. By the time it leaves the last pond, the water’s pH has returned to normal, and the now-clean water enters the stream. The bright orange-yellow color that lines the bottom of the ponds is iron sludge that is eventually scooped up and moved to drying beds.

Success Story

Fred Lockard lives at the other end of Morris Drive, downstream from Mike and Eddy, in the house he’s occupied since 1969. “I’m extremely proud of this creek. We’ve got crawdad, we’ve got salamanders. We’ve got a crane about this big,” he says with arms stretched wide. “There is so much more wildlife today than there was when I was a kid.”

“Mike and I played in the creek and most all the kids did,” says Eddy. “But the last 30 years prior to us starting this, that didn’t exist. We just took the initiative so our kids and our grandkids can enjoy the things that we did.”