“Too many governments have failed to adhere to basic norms of institutional rationality and transparency, too many people — often influenced by misinformation — have disrespected and protested against basic public health precautions, and the world’s major powers have failed to collaborate to control the pandemic,” said the authors, working under the auspices of one of the world’s leading scientific journals.

The LancetCOVID-19 Commission, formed to foster equitable and lasting global solutions to the pandemic, held its first meeting in June 2020. The commission worked with 12 task forces with expertise in areas including public health, vaccine development, health diplomacy and school and workplace safety.

A “lack of ambition” in the global pandemic response, resulting in the loss of more than 17 million lives worldwide, is the latest example of the inability of nations to work together to address pressing global challenges such as climate change, the report concludes. Its most basic recommendation is that multilateralism be strengthened.

This strategy has relevance to the obstacles health officials in America face as they work to manage COVID-19 and prepare for future outbreaks.

The U.S. may be the world’s wealthiest country but its public health infrastructure, a patchwork of under-funded state-led systems, is inherently unsuited to national collaboration. Significant disagreements among state leaders about COVID-19 science and policy and demands for “medical freedom” make a unified effort even more difficult.

“It’s not exactly the same, but if you think about us as 59 different states and territories, the issue of consistency between different governments, the issue of agreeing on shared policies, the issue of communication across borders applies,” says Michael Fraser, executive director of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO).

(Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times/TNS)

Struggles at the State and Local Level

The consequences of poor coordination are most keenly felt by local health departments, where decisions must be made to prevent the spread of disease, says Lori Tremmel Freeman, chief executive officer for the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO).

A lack of coordination existed throughout the pandemic, says Freeman, made worse by the injection of politics. Local officials were left “holding the bag,” delivering public health orders without support from elected officials anxious to appease their constituencies.

Some state legislatures took things a step further, introducing legislation to limit the authority of public health officials. More than half of the states in the U.S. have passed laws restricting public health powers, from banning masks, vaccine mandates and vaccine passports to shifting public health decisions to elected officials with no scientific expertise.

Every state has at least entertained such measures, says Freeman. “Nobody is against checks and balances, but you can’t remove public health authority on a wholescale basis based on a pandemic where you didn’t like how public health orders affected your personal freedoms.”

This kind of pushback has also thwarted pandemic response in other countries. The Lancet Commission noted a low ebb of “prosociality,” voluntary behavior by individuals for the good of all, in support of public health rules and guidelines.

The pillars of effective response to infectious diseases are prevention, containment, health services, equity and the development and distribution of vaccines and therapeutics, the commission asserts. But these depend on prosociality as the framework for personal and governmental action.

“The question that was called in this pandemic is whether we as a society are willing to subjugate individual needs for the greater good,” says Brian Castrucci, president and CEO of the de Beaumont Foundation. “In far too many places in the U.S., we answered ‘no.’”

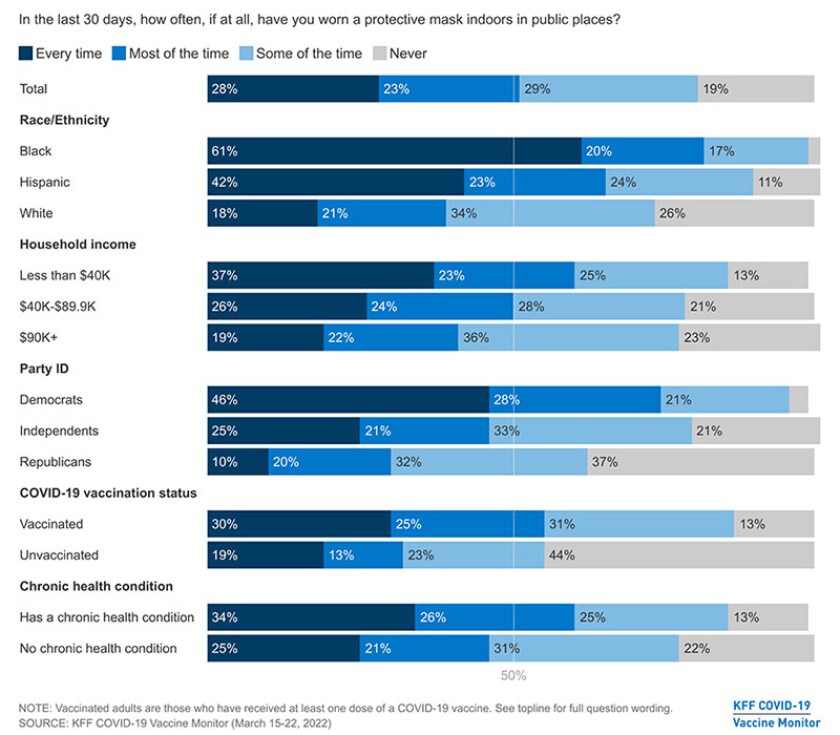

(KFF)

The Problem With Low Health Literacy

A July survey by Pew Research revealed how much attitudes regarding personal choice in following public health guidelines diverged along party lines. Almost 7 in 10 Republicans felt that too little attention had been paid to “respecting individuals’ choices” during the pandemic, more than twice the number of Democrats who had this view.

It’s as if individualism has emerged as a new determinant of health, says Castrucci. “The ‘pull yourself up by your bootstraps’ mythos is central to this country, but no one does anything by themselves. Somehow, that understanding has been lost,” he says.

The commission highlights “low health literacy” as a factor in public rejection of public health measures that were both routine and effective. Low levels of both general literacy and health literacy have been recognized as public health problems since the 1990s, says Rima Rudd, senior lecturer on health literacy, education and policy at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“Yet little progress has been made in adjusting our health communication to what the data indicates,” she says. “We professionals have done a poor job sharing our data, our findings, our information — we have made information available but not accessible.”

“I would have assumed that in a global catastrophe that had the mortality and morbidity of something like COVID, we that we would rally together against it,” says ASTHO’s Fraser.

“We’ve always managed to come together in public health situations and the fact that it didn’t happen should concern us all.”

One of the Lancet Commission’s critiques of the global pandemic response is that public policies failed to draw on the social sciences. Fraser, trained as a physician and a social scientist, observes that it’s not always that people don’t believe the scientific data presented to them. Often, they are making decisions using some set of criteria other than data.

“That’s where we failed to really understand the nuances,” he says. “Who the messenger is, what the message should be, should vary by community.”

(Doug Duran/TNS)

National Assessment

To date, there’s been no comprehensive assessment of U.S. state and federal pandemic response, Fraser says. “Unfortunately, there’s very little interest because it was so political that nobody wants to weigh in on it.”

Castrucci sees the lack of a coordinated response as the “ugly side of federalism,” creating a situation where every state had a unique response to a virus that followed only one set of rules. He is especially critical of political leaders who introduced doubt about the COVID-19 vaccine or the virus itself.

While Castrucci acknowledges that it’s hard to characterize a million deaths from a preventable disease or the current “handle it yourself” policy as public health successes, he doesn’t place blame on public health workers. “They threw everything they had at this, but we didn’t give them enough to throw and the bill came due.”

Fraser “categorically denies” that the public health response to a virus that had never been seen before was a failure. The fact that a vaccine was available within a year, being administered to 3 million people a day, is something that should be celebrated, he says. The notion that public health needs to be entirely rethought and reimagined is a disservice to the public health community.

“I don’t think the issue was the public health prevention and mitigation efforts; it was how they were interpreted and responded to by policymakers,” he says.

The local government public health workforce was depleted by more than 20 percent before the pandemic hit. More workers departed during the pandemic, and Freeman expects the trend to continue.

Those who remain are just now crawling out of the cloud of pressures, threats, long hours and low pay that they’ve been in, she says. “It’s really hard for them to get into the space of, ‘Okay, I made it through, now how can we do better?’”

Even so, NACCHO and others have been holding action review meetings to identify where changes are needed. The Biden administration has committed billions in rescue funds to shoring up the public health infrastructure, but Castrucci cautions that in many cases this money will go through governors who opposed pandemic restrictions and support laws to limit public health authority.

“A governor has more impact on your health than your doctor or your nurse,” he says.

A Different Kind of Failure

It’s not just a matter of identifying better ways to manage the remaining stages of the pandemic or future public health emergencies, says Freeman. The most fundamental missing ingredient is a national system of care that integrates both public health and health care.

The National Institutes of Health currently has an annual budget just over $45 billion, most of which is spent on research. Freeman would like to see a similar investment of public dollars to prevent the emergence of illness.

“We’re not paying enough attention to emphasizing prevention and wellness over sickness. That is the real failure of our country.”

Related Articles