Since Los Angeles Unified earlier this month became the first large school district in the United States to order all eligible students be vaccinated against COVID, a small but growing number of districts have followed, including Oakland Unified this week.

On Thursday, the secretary of California's Health and Human Services Agency suggested a statewide mandate was under consideration, though no action was imminent. School vaccines mandates are "not unusual," said Dr. Mark Ghaly, the health secretary, during a news briefing Thursday. "We actually have a long tradition ... of vaccine requirements in schools."

But in the past, vaccine mandates have come almost exclusively from state legislatures.

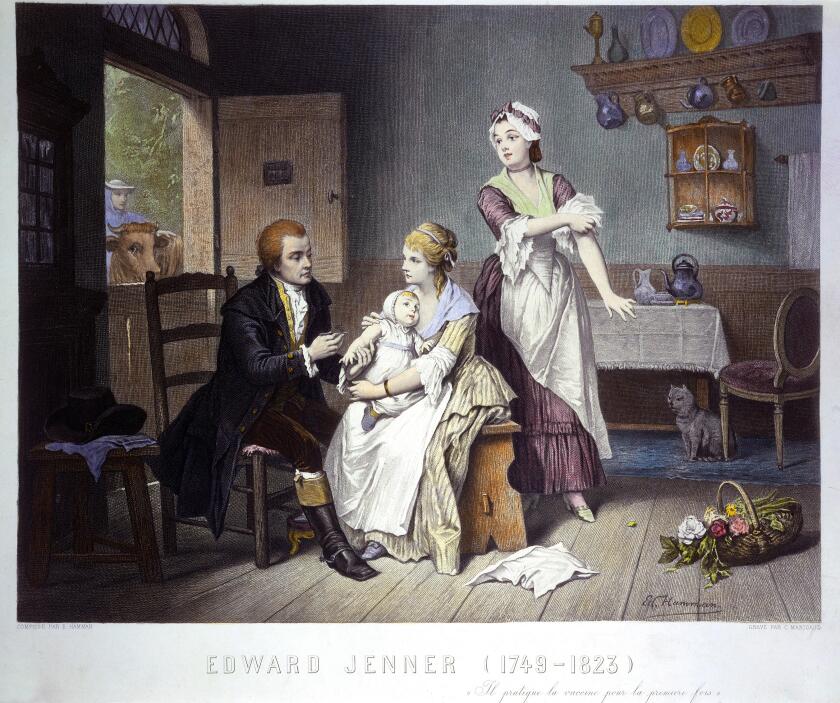

In the 19th century, some local schools or counties ordered smallpox vaccination for children, but since then mandates have always come from state legislation, not local, state or federal health orders, and not from school districts. And the mandates arrived not amid an evolving global crisis, but after decades or longer battling a well-established disease and years of vaccine development.

"Not since smallpox have we seen requirements like this," in a patchwork fashion across the state, said Dr. Loring Dales, who ran the immunization branch of the California Department of Public Health for nearly 30 years before retiring in 2003. "There have been furious debates for other vaccines in schools — some parents would want something new to be required and other parents would not. But it just didn't happen."

California's childhood vaccination mandate was established in the 1920s; at the time, it only required students get shots for smallpox before entering school. But it set a framework to add more vaccines as they were developed and federally licensed. Currently, K-12 students are required to be vaccinated against nine infectious diseases, including polio, measles and, most recently, chickenpox, which was added in 2001. Smallpox was dropped as a requirement in the 1960s, after the virus had been eliminated in the U.S.

The goals of school vaccine mandates go beyond simply protecting children from harmful and even deadly disease. Mandates can prevent school outbreaks, which can force principals to send home entire classrooms or shut down campuses. They also improve community-wide immunity, which can slow down the spread of disease across all age groups.

School requirements provide a "catch-point" to get everyone vaccinated against diseases that spread in other parts of the world, said Dr. George Rutherford, a UCSF infectious disease expert and former California health officer. Measles has largely been eliminated in the United States because, for more than 40 years, every kindergartener in every state has been required to get vaccinated.

"Mandates work, because most people want their kids to go to school," said Dr. Art Reingold, a UC Berkeley infectious disease expert. Some parents may be hesitant, and if they had the option they might not vaccinate their children, but under pressure they'll go along with it, he said. "You can argue whether mandates are OK or not from a moral or ethical or political point of view, but they work."

Traditionally new vaccines are added by the state legislature, after years of safety and efficacy studies, and once scientists have worked out details, such as at what age children should be vaccinated and how many shots they'll need.

Many health and legal experts said it's premature to expect that process to be applied to COVID vaccines before the end of this year. A vaccine hasn't yet been approved for children under 12 — authorization is expected as early as next month for kids age 5 to 11. And for children 12 to 15, the Pfizer vaccine — the only one available for the age group — is still under emergency authorization and not yet fully licensed.

There's scant evidence of whether children will need boosters or which vaccines work best for them. And at least so far, it appears that schools are able to open safely and prevent most transmission with masks and other protective efforts — meaning there doesn't appear to be an urgent need statewide to order vaccination to keep children in classrooms, some policymakers said.

"For school-aged kids, I think we still need to get more information," said state Sen. Richard Pan, D- Sacramento, who has introduced legislation tightening school vaccine mandates in the past, and is seen as the most likely to bring up similar legislation for COVID at some point.

Pan said he supports school districts moving ahead with mandates if they believe the local situation warrants it; he wrote a letter backing Los Angeles Unified's Sept. 9 decision.

"But in terms of a statewide law, we're not quite there yet," he said. "If something really dramatic happens, if this fall suddenly everything explodes in schools, then there is a conversation to be had," he added. That would include input from the governor, he said, and would require a special session of the legislature, which is on recess through the rest of the year.

Any other means of ordering school vaccinations — statewide or local — would be unprecedented and likely face legal challenges, said Dorit Reiss, an expert in childhood vaccinations at UC Hastings College of the Law. That would include the state health department issuing a mandate for all eligible children, as well as mandates from school districts or county health officers.

The state health department already has required teachers across California be vaccinated against COVID or tested weekly. But a mandate for students likely would be a more volatile issue, and state health officials might be reluctant to take that approach without the public feedback that's part of the legislative process, said Dr. Dean Blumberg, chief of pediatric infectious diseases UC Davis Children's Hospital.

"I can imagine if they did it by fiat that there would be a backlash," he said.

Clearly some districts have already decided to gamble on mandates. Reiss said county health officers may do the same. "It's unprecedented, and that would make anyone hesitate, but they've been doing unprecedented things for a while," Reiss said. "Even the mask orders were legally new, and they did them anyway."

At least so far, no county health officers appear eager to order all children vaccinated, even in places like San Francisco that have issued mandates for adults in many spaces and occupations. In the Bay Area, part of the reason may be generally high vaccination uptake among children 12 and older who are already eligible; in some counties, more than 90 percent of that age group is at least partially vaccinated.

Before they issue orders, health officers may prefer to see if they get similarly high rates among 5- to 11-year-olds once they're eligible.

"We've been very careful to use the health officer authority at the local level in places where we feel like there are things that can't be done by others. We've tried to be judicious," said Dr. Nicholas Moss, the Alameda County health officer. "That plays into not just schools, but all of our policy considerations."

In his county, school districts in Oakland and Piedmont have vaccine mandates for children, and Hayward will require kids to be vaccinated or tested weekly. "That's certainly reasonable" for educators to make decisions that directly affect their school community, Moss said. "We're glad to have kids back in schools, and we think it is happening safely and can be done safely," he said. "This conversation about children getting vaccinated is going to play out over some time."

Oakland Unified's mandate, approved Wednesday night, does not yet set a deadline for when students must be vaccinated, and the superintendent said it was unlikely to be implemented before the end of the year. Los Angeles Unified is requiring all students 12 and older to be fully vaccinated by Jan. 10.

In districts that have moved ahead of the state with mandates, supporters have said they felt an urgent need to get every child vaccinated to prevent outbreaks, protect the greater community, and keep students from becoming infected and missing school or suffering severe illness, which is an unusual but not unheard-of outcome in kids.

"This decision wasn't made lightly. It was made first and foremost to maintain safety in our schools," said Dr. Smita Malhotra, medical director for Los Angeles Unified, who added that seeing pediatric hospitalizations climb in other parts of the country raised further concern that the need to vaccinate was urgent. "A lot of our students come from communities that have been largely impacted by the pandemic. By making this decision we would prevent further hospitalizations and trauma for our students."

"Our goal is to get back to normalcy at some point," she said. "So we are using every tool in the toolbox to get there."

Marin County parent Carl Krawitt offers his own community as an example of just how powerful a tool school mandates can be. In 2015, his family led a rebellion against a loophole in the state law that allowed parents to easily opt out of vaccinating their children — a loophole that had resulted in a significant drop in vaccination rates and was blamed for the largest measles outbreak in California in 25 years.

At the time, Krawitt's son, Rhett, was recovering from treatment for leukemia, and due to his depressed immune system, he couldn't be vaccinated against measles. Krawitt was furious that parents in Marin County — then a hotbed for anti-vaccination attitudes — were not vaccinating their children and putting his son at risk. He worked with Sen. Pan to pass legislation that did away with "personal exemptions" that made it easy for parents to choose not to vaccinate their kids.

In the years since, vaccination rates in Marin County climbed from 85 percent for incoming kindergarteners to nearly 95 percent. And the county — once famously mocked by comedian Jon Stewart as home of "science-denying affluent California liberals" — has among the highest COVID vaccination rates in the United States: 97 percent of eligible residents have had at least one shot.

"People's hearts and minds were changed because of mandates," Krawitt said. "Public opinion changes when you pass a law about something."

(c)2021 the San Francisco Chronicle. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Related Articles