The greatest share of this money, $42.5 billion, will be distributed through the Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment (BEAD) Program. Each state will receive at least $100 million, with additional funds granted according to the number of “unserved” locations in it (those without reliable service of at least 25 Mbps download and 3 Mbps upload).

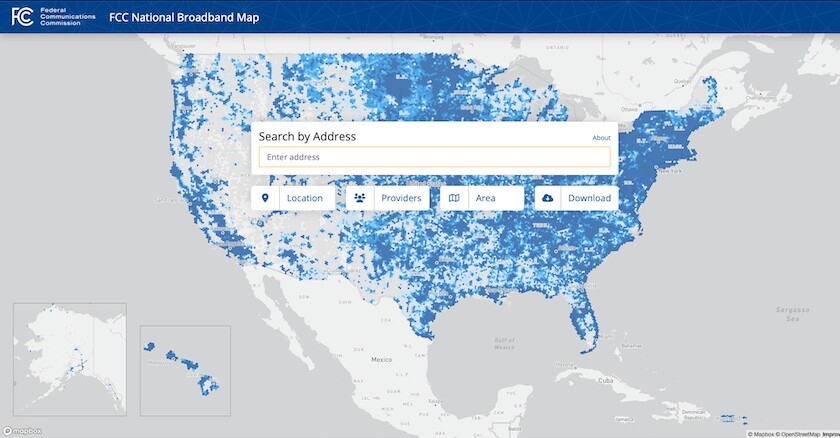

On Nov. 18, the FCC unveiled an update of its map showing broadband availability in communities throughout the U.S. NTIA is required to use this map to identify unserved locations eligible for extra funding, based on both service availability and the number of locations in any given area.

Congress gave NTIA funding in 2018 to work with FCC, state and local governments, nonprofits, network operators and other stakeholders to improve its data. A 2021 report from Next Century Cities found that FCC data “perpetually overstates broadband availability.” It documented instances in dozens of states and territories where data from other sources greatly contradicted the picture painted by FCC’s coverage map.

“Equity starts with universal availability,” says Kathryn de Wit, director of the Pew Charitable Trust’s broadband access initiative. “We have to know where connections are, and are not, in order to understand the full breadth of the availability challenge that we are facing.”

Pew, Next Century Cities and others have worked hard to help communities fill gaps in the FCC map, but it’s an enormous task to create a truly granular picture of broadband coverage. Early responses to the FCC release from groups focused on broadband access suggest that there’s still potential for jurisdictions to miss out on funding because of incomplete or inaccurate data.

Looming Deadlines

Dustin Loup oversees the National Broadband Mapping Coalition, a collaborative effort organized by the Marconi Society, where he works as program manager. Loup lives in Washington state. He is also assisting the Washington State University Extension program’s work to expand rural broadband access.

“I’ve been scrolling around to random spots and finding tons of missing locations in unserved areas,” he says. “It is very bad on tribal lands.”

A truly accurate map would reflect several characteristics: the number of homes or businesses in a specific area (described by the term “fabric”) and what kind of service, if any, is available in it. Ideally, this would include the actual speed of upload and download, not the advertised speed, and the cost.

Now that the map has been published, the FCC will accept challenges to its fabric and coverage data on a continuing basis. But the deadline it has announced for coverage challenges that can be matched with fabric updates, and reflected in the version of the map used for BEAD allocations, is Jan. 13.

Loup doesn’t believe this is enough time. “This is typically the hardest window of time to get anything done.” Moreover, he says, the challenge process requires skill sets and technical expertise that might be common among Internet providers but not local governments.

“Let’s say we find a thousand missing locations in Washington state, and we file a challenge three weeks from now,” Loup says. “That challenge is not going to be processed ahead of the vintage of the map released when providers start reporting.”

The missing locations would not be linked with the best data about availability and not considered in BEAD allocations.

Despite such difficulties, there are things that can still be done between now and the January deadline to improve data informing the distribution of BEAD dollars.

(Antonio Perez/TNS)

Filling Gaps

“If we’re going to set deadlines that are too short for meaningful challenges, why aren’t we making every effort possible to use all of the information that is available?,” asks Francella Ochillo, executive director of Next Century Cities. “Why aren’t we using speed test data, American Community Survey data or training concerned citizens to launch their own interventions, doing everything possible to make sure people can contribute?”

Ochillo’s group supports local officials on an ongoing basis, sharing practices that have helped cities and states upgrade FCC data about broadband in their communities. It encourages them to contact the FCC’s intergovernmental affairs office, tasked with helping state and local governments understand its programs.

Christopher Mitchell, director of the community broadband networks initiative at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR), says it’s especially important for rural areas to make sure their fabric is correct, and for any community to do what it can to make sure the services claimed to be available to it really exist. “In my area, there’s a company that claims to deliver symmetrical gigabit wireless service, and it’s a phantom.”

The FCC could be doing even more to help states and municipalities learn how to launch a successful challenge, Ochillo says. It’s easy to make assumptions about the ability of local officials to participate in FCC’s process, but the majority don’t have the expertise to fulfill its requirements for a data challenge. “The people who can’t get in are going to be stuck with poor data — and not only poor data, but insufficient resources.”

Pew’s de Witt has also heard Internet service providers say that FCC’s data submission process is challenging and its portal difficult to use. “Improving our data quality also means improving the user experience and improving the quality of the interface and platforms to ensure that it’s easy to submit information,” she says.

It’s also important that NTIA gets planning funds out to states in a timely manner, so that they have the resources and administrative support necessary to engage in the challenge processes it has designed. There’s an opportunity to demonstrate their potential to work in favor of the underserved and to improve outcomes from spending.

“While all of this is frustrating for folks at just about every level of government, the fact that we now have a challenge process in place at the federal level is a step forward,” says de Witt. “These are important steps in accountability for spending that states have been using for years.”

Beyond the Map

Mitchell doesn’t doubt that some local governments might not get as much money as they would if FCC maps were better. “I don’t think a state is going to have twice as much or half as much assigned to it depending on variances within the FCC data,” he says. “It might be more like three to five percent.”

The most important thing for local governments at this point, Mitchell says, is to make sure they have a voice in the process to determine who gets grant funds in their area.

“When the eligibility is sorted out, there will be a period where applicants can apply for funds to provide service to parts of the state that are underserved — at that point, cities should be able to say, ‘We have a strong preference for this applicant and not that applicant,’” he says.

Past decisions by the FCC to require jurisdictions to use a certain provider have worked to their detriment, Mitchell says. If states are considering such rules, local governments need to be at the table to make sure that whatever is decided is a true solution for them.

Cities will continue to be at a disadvantage in any planning or negotiation if they don’t develop broadband expertise. “If you call a department of public works anywhere in this country and a random person picks up the phone, they would be able to tell you the difference between concrete and blacktop in terms of how each will weather and the length of the return on investment.”

By comparison, few cities have people who know enough about broadband to recognize infrastructure that belongs in the past, or to collect persuasive evidence to push back if service from a provider is nowhere near true broadband speed. Cities can’t avoid becoming specialists, Mitchell says. “They need to take this seriously.”

If they don’t, the consequences could be far reaching. The pandemic deepened community understanding of the importance of broadband. This has provoked some to form coalitions to plan robust systems, nothing less than fiber, says Angela Siefer, executive director of the National Digital Inclusion Alliance.

They will be more economically stable, more prepared for the future as a result. “It’s not just going to be their broadband, it’s going to affect every other aspect of those places — which companies come to town, who stays in town, whether young people stay when they graduate or leave,” says Siefer. “There will be rural communities that really thrive because they have set all this up.”

Looking ahead, local leaders also need to keep in mind that the billions disbursed through BEAD will create a need for bigger investments in other aspects of digital equity, such as devices, technical support and programs to develop digital skills. “We know that’s a piece that never goes away,” Siefer says.

Related Articles