Firearm homicide rates also increased over the period, by 18 percent. Mass shootings in 2022 have understandably provoked outrage, but more than half of all gun deaths in the U.S. are the result of suicide.

Suicide itself is a greater factor in premature death that may be commonly understood. According to the CDC, in 2020 it was the second leading cause of death (after unintentional injury) for Americans ages 10-14 and 25-34. Among those 15-24 it was third (just behind homicide) and for those 35-44 it was fourth.

Guns add a lethal dimension to this public health problem; a study published in Annals of Internal Medicine that looked at millions of records from hospitals and emergency departments found that while less than 9 percent of all suicide attempts were fatal, nearly 90 percent that involved firearms resulted in death.

The city-level findings are outlined in the report Gun Suicide in Cities, a collaboration between the nonprofit Everytown for Gun Safety and New York University Langone Health. The firearm death data has been incorporated into a City Health Dashboard from Langone Health that includes more than 40 measures of health and health equity.

“When we think of firearms in cities and the harm they cause, our minds tend to go straight to the shooting of others,” says Marc Gourevitch, chair of the Department of Population Health at NYU Grossman School of Medicine and principal architect of the dashboard. “One lesson from this analysis is that it is important to focus attention on reducing the availability of guns to people who might be considering suicide.”

Fewer Policies, More Deaths

Nationally, the rate of suicide deaths increased by 12 percent between 2010 and 2020, according to an analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), accounting for more deaths than motor vehicle accidents.

White Americans were more than twice as likely to commit suicide as Blacks, though the rate among African Americans increased from 5.4 to 7.7 per 100,000 over the decade. The greatest increase over the period, 62 percent, was among those ages 12-17.

Heather Saunders, a postdoctoral health services researcher for KFF, published her findings regarding the prevalence of gun suicides in these trends in July of this year, the month when a three-digit national suicide and crisis dialing code, 988, went live.

Saunders looked at suicide rates at the state level and saw substantial variation across states. “When we broke it out by the type of suicide and included suicide by firearms, I noticed that the variation seemed to be driven by firearm suicide rates.”

Next, she consulted the State Firearm Law Database and sorted states into groups according to number of gun law provisions, assigning them to “low,” “medium” and “high” categories. (The categories were based only on the number of laws, not the type.)

The states with the fewest number of gun laws had the highest rate of gun suicides, two times higher than those in the “high” category. Saunders estimated that if all states had the rate of firearm suicide deaths she found in states with the most gun laws, 15 percent of all suicide-related deaths might be averted.

“My study is not designed to be causal,” says Saunders. “It’s simply looking at two things that are happening at the same time.”

Laws may not be the only factor affecting how easy or hard it is for persons contemplating suicide to access a firearm. But the city-level analysis by NYU and Everytown found a similar relationship between policy and death rates.

Understanding Determinants

“We cannot fully address city gun violence until we acknowledge the growing and often unspoken role that gun suicides play in our country's gun violence epidemic,” says Megan J. O’Toole, deputy director of research at Everytown for Gun Safety.

Analysis of CDC data for more than 750 cities of 50,000 people or more found that 4 in 10 suicide deaths in them were caused by firearms, 7,000 deaths per year.

Cities in states with strongest gun violence prevention laws had half as many gun suicides as those in states with the weakest laws, paralleling the KFF findings. “Strength” was determined according to a state gun law ranking system developed by Everytown.

The prevalence of gun shops had an even stronger association with deaths from gun suicides, with rates four times higher in the highest range (more than 10 shops per 100,000 residents) than the lowest (fewer than 3 per 100,000).

In cities with a scarcity of walkable neighborhoods or parks, rates of gun suicides were higher — twice as high as in those with the largest amounts of green space.

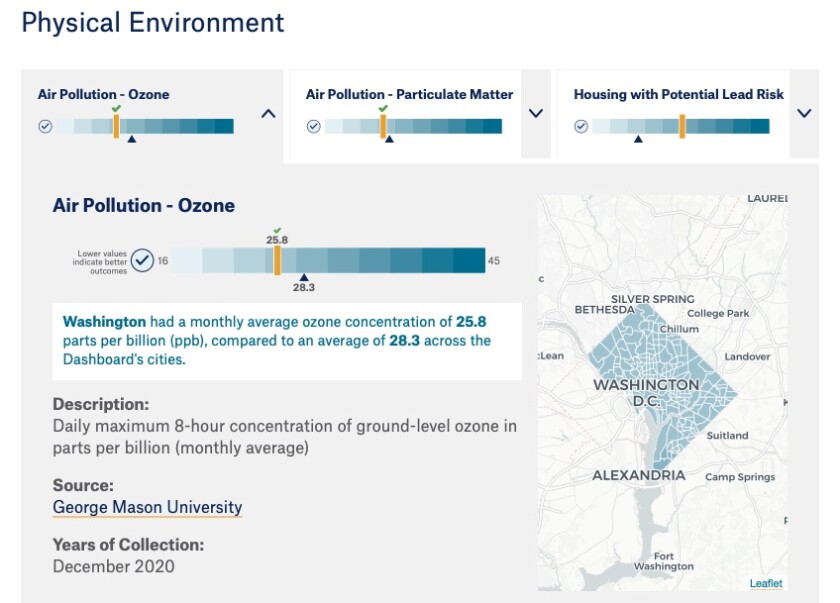

Park access and walkability are among the metrics included in the City Health Dashboard. The inclusion of firearm data in the dashboard allows city planners and health officials to examine relationships between their gun violence numbers and other social, health and environmental metrics. These can be viewed at city or census tract level.

One place to start might be life expectancy, says Gourevitch. “There’s a lot that goes into life expectancy, and sometimes the variation can be quite significant across neighborhoods. That can spark a conversation about what could be driving that, and then one can turn to other measures.”

Prevention

Strategies for keeping guns away from those considering self-harm are well understood, and not all require legislative action. Safe storage practices are essential. As of 2021, only 14 states had safe storage or gun lock requirements. Whether such laws are in place or not, gun owners bear major responsibility for safe storage.

Everytown’s Be Smart campaign offers a variety of training resources regarding safe storage that jurisdictions and local organizations can use, and its volunteers routinely provide training in communities. Gun shops can contribute to educational efforts, says O’Toole, and provide third-party storage.

Extreme Risk Protection Orders, also known as “red flag” laws, create a legal mechanism which includes due process by which firearms can be removed from persons who have threatened violence against themselves (or others). Nineteen states have enacted such laws.

Gourevitch notes that a majority of people who attempt suicide have seen a health professional in the month before their attempt. Opportunities to screen for symptoms are being missed, and services need to be available to those in distress.

Barbers, beauticians, friends and family are also part of the prevention infrastructure, says O’Toole. “We all have a part to play in reducing gun suicide.”

If you know someone who is thinking about suicide, help is available at 988, the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.

Related Articles