More than half of the respondents say the pandemic has left them with one or more symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, with one in four experiencing three or four such symptoms. Four out of 10 have been “bullied, threatened or harassed” by persons outside their health departments.

It would be a mistake to view the responses to the survey as a warning or a call to action, says Brian Castrucci, executive director of the de Beaumont Foundation. “They're an alarm,” he says.

“The very people that we trust with protecting us — who we generally ignore most days and have ignored throughout a pandemic — are leaving,” says Castrucci. “After experiencing the worst public health pandemic in the past hundred years, we are more vulnerable than we were at the start.”

The de Beaumont Foundation and the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) collected responses from nearly 45,000 state and local health department employees between September 2021 and January 2022. The findings of their Public Health Workforce Interest and Needs Survey (PH WINS) have just been published.

(de Beaumont Foundation/ASTHO)

Messaging and Reality

The recently published National COVID-19 Preparedness Plan focused on a return to normal routines. The strategies it outlines to accomplish this cannot be executed without a stable, well-funded public health workforce that has the support of state and local leaders.

As much as America might be ready to be done with COVID-19, it remains to be seen whether the virus is done with it. At present, case rates in most Western European countries are high enough for them to be considered COVID-19 “hot spots.”

Omicron propelled U.S. cases to the highest numbers ever seen less than two months ago. The surge in Europe is attributed to a variant of omicron, BA.2, that appears to be even more contagious. BA.2 is already spreading in the U.S., and levels of coronavirus in wastewater systems, another indicator of contagion, are on the rise in some parts of the country.

This doesn’t mean it’s inevitable that the U.S. will see another surge. “I don’t think we will,” Anthony Fauci said on ABC’s “This Week.”

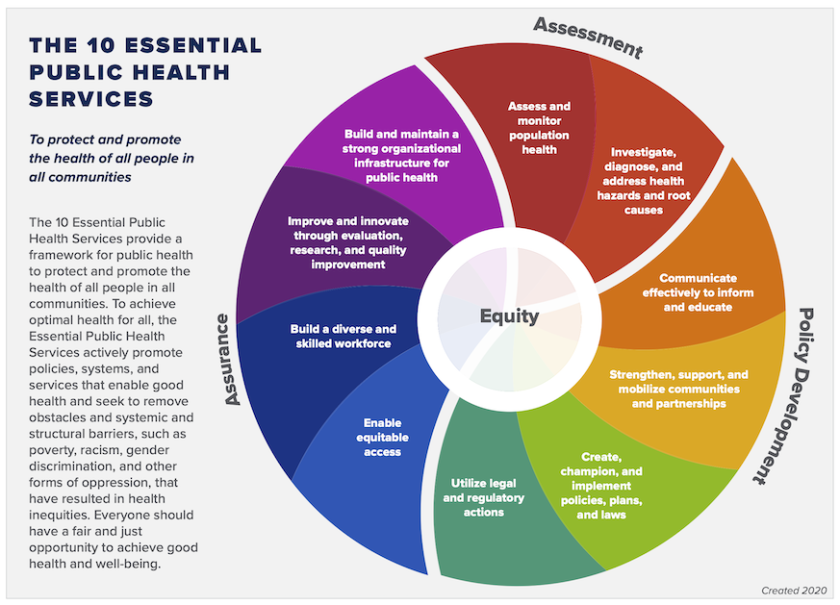

Any return to “normal” life will depend on the work that public health workers do to identify outbreaks of COVID-19 and future variants in their communities, develop policies and plans to address them, and enforce laws and regulations created to protect community health.

If almost half of all physicians, rather than public health officials, were thinking of leaving their jobs in the next five years, there would be congressional hearings and immediate action, says Castrucci. “We are slowly but surely eroding the pillars that keep our nation standing and doing nothing about it.”

(de Beaumont Foundation/ASTHO)

Moral Injury

The hostility expressed toward public health workers constitutes a form of moral injury, says Michael Fraser, the CEO of ASTHO. This concept, first applied to veterans, refers to the harm caused to persons involved in events that go against their deeply held beliefs — whether they are forced to violate moral or ethical rules or are punished or shamed for actions taken in good faith.

Fraser believes moral injury can be as big a factor as overwork or stress in driving workers from public health. Anti-government sentiment is strong among those most vocally challenging their work; two in 10Americans believe that vaccination, the most important weapon in the pandemic war, is a government conspiracy to microchip citizens. “Who’s going to want to work in a health department?” says Fraser.

Harassment of those attempting to implement public health measures has reached unprecedented levels. Lisa Macon Harrison, health director for Granville Vance Public Health and president of the board of the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO), has been told by citizens that if public health mandates prevent them from living out their freedom, the Second Amendment gives them a tool to do so. (As an example of this trend, in this recording from a school board meeting, a Virginia parent threatens to bring loaded guns to her child’s school to protest its mask mandate.)

In October 2021, U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland asked federal authorities to work with local law enforcement to find ways to do something about harassment and intimidation of school officials. Within days, the CEO of NACCHO, Lori Tremmel Freeman, wrote to him asking that protection of local public health officials and staff be included in these discussions, citing threats to them from community members and armed anti-government militias, as well as politicians.

Macon Harrison recognizes that being a public servant means serving everyone, regardless of their politics, activism or opinions about her. “That’s part of what you understand when you take on a role as a public servant, but death threats, publishing of home addresses of public health workers and online bullying should not be part of the mix.”

The consistency of messages across states suggest that the aim is not just to make the lives of public health officials miserable, but to attack and discredit public health authority, says Fraser. In 2021, Republican legislators in at least 26 states enacted laws limiting the authority of public health officials to take action to limit the spread of infectious diseases. NACCHO CEO Tremmel Freeman points to model language developed by the American Legislative Exchange Council as the inspiration for many of these bills.

“Rather than having a conversation about when we are willing to say that the collective good overrides our individual needs, folks are looking to change the law so they can make that choice whenever they want,” says Fraser. “That is scary.”

(de Beaumont Foundation/ASTHO)

Undeterred

Despite all, the PH WINS survey also reveals that the vast majority of public health workers believe their work is important (94 percent) and are determined to do their best each day (93 percent). Almost eight in 10 say that they are satisfied with their jobs.

Retention of these workers must be a focus, says Castrucci, using strategies including better HR systems and programs to repay loans for the advanced degrees required for many public health positions. “You can't leave a master's program in public health with $70,000 or $80,000 of debt on top of your undergrad [degree] and work for $30,000 a year.”

The return on investing in the public health workforce might be considered against the costs the U.S. has borne due to the pandemic. On the basis of the value assigned to lost life, this figure is approaching $10 trillion.

Macon Harrison has seen the beginnings of collaboration between organizations such as NACCHO, the American Public Health Association and state attorneys general. “How can we work in concert to ensure that we keep a skilled, dedicated public health workforce in place over time?”

A lack of public understanding about what public health is and does, and what makes it different from health care, is another challenge. While stimulus money might not be a way to fund salaries, some states could use federal funds for outreach and education. This money does run through governors, Castrucci notes, and those who have not been supportive of public health measures during the pandemic might not be willing to make such investments.

An earlier report from the de Beaumont Foundation, in partnership with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, used interviews and focus groups to define ways that businesses and chambers of commerce could align with public health officials toward the shared goal of healthy communities and a healthy local economy. In addition to defining steps forward, it revealed confusions about public health entities and the right channels for contact and communication.

It's time for political and community leaders from both sides of the aisle to speak up in defense of public health, says Castrucci. “We are allowing a very small minority of bullies to run people out of this profession.”

Macon Harrison wants to see more voices of influence come forward from health care and academic centers to foster better understanding of communicable disease and the historical basis for quarantine and isolation. These could counter the perception of public health as interference with personal liberty.

“People aren’t thinking through all the way to the end of the scenario,” she says. “If we reduce our ability to do public health community by community, if we are not able to fight disease, that has a lot more threat to our freedom as Americans in the long run."

(de Beaumont Foundation)

Related Articles