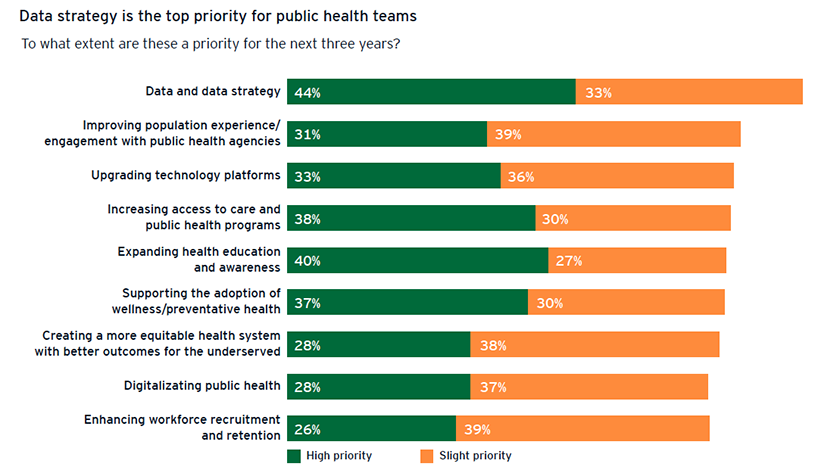

Only about 4 in 10 of the respondents involved in delivering public health services shared this view, however, and the same low percentage felt that more automation was key to innovation and change. “I think they have an appreciation for the data and the data strategy, but when you’re operational you’re in the weeds, just trying to get things done,” says Belinda Minta, EY US Public Health Services Transformation leader.

The survey report notes that this “gulf in perception” between leadership and operational teams could stand in the way of change. Eighty-five percent of decision-makers consider it to be a “silver lining” that the pandemic had revealed weaknesses in public health operations that could point the way to change, but less than 40 percent of those in delivery feel this way.

So far, the enthusiasm leaders express for technology upgrades has not been translated into action, EY US found. “When it comes to implementing new technology, just one in three (34 percent) is pursuing root-and-branch upgrades of their IT systems, and a mere 10 percent are integrating this activity into a transformation of their wider systems.”

This is not unexpected. However citizens might see things, the pandemic is not over for public health officials. Change at the scale that is needed has been building for years, but progress depends on their ability to get beyond the demands of emergency response.

(Ernst & Young LLP)

A Public Health Superhighway

In September 2019, before the first COVID-19 case was reported in the U.S., the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) published a report calling for a “public health data superhighway” capable of detecting health challenges and informing the response to them.

The technology to accomplish this already exists, CSTE noted. But even so, “public health departments struggle to take advantage of these advancements and continue to rely on sluggish, manual processes like paper records, phone calls, spreadsheets, and faxes requiring manual data entry.”

The limitations of this data ecosystem became a considerable liability when public health officials ran up against a virus that had never been seen before, working to both understand and control it at the same time. “There were mixed messages, and the pandemic made us look like our data was not adequate to the task,” says Gail C. Christopher, executive director of the National Collaborative for Health Equity.

This provided an opening for political or social actors to push anti-public health campaigns that continue to fuel public distrust of public health leaders, workers and guidelines. Reliable and timely data could help heal some of the harm that has been done, says Christopher.

“I think every health department has aspects of a complete data system,” says Brian Castrucci, president and CEO of the DeBeaumont Foundation, which funded the CSTE report. “But we need to articulate what a complete data system looks like — right now, we don’t even know what the destination is, so it’s hard to tell when we’re lost.”

A Data Modernization Movement

Data systems improvement is one of three major topics that recur in discussions about rebuilding public health, along with workforce expansion and regaining public trust, says Michael Fraser, executive director of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO). “A major finding from all the conversations that we’ve had about COVID is that data systems need to be modernized.”

In recent years, there has been considerable effort by the public health community to find ways to move away from “silo-based” or disease-based surveillance between states and the federal government to an enterprise-wide system, says Fraser. “During COVID, a lot of states had a hard time sharing data, and there are many parts of this country where people go back and forth between multiple states on any given day — it’s not just the ability for states to share data with the federal government, but for states to share amongst themselves.”

The CDC’s Data Modernization Initiative, launched in 2020, is a $1.2 billion effort to address this challenge, envisioning resilient, connected systems that could “solve problems before they happen and reduce the harm caused by the problems that do happen.” The CSTE campaign “Data: Elemental to Health” is working to ensure sustained public funding for this work.

In May, the Healthcare Information Management Systems Society published its estimate that it would take $36.7 billion over the next 10 years to modernize the country’s state, territorial, local and tribal public health infrastructure — $25.6 billion for data infrastructure and $11 billion for interoperability and sustainability.

“The issue isn’t necessarily getting states to do everything the same way, the issue is getting a layer on top of that, that can translate and standardize data for aggregation purposes,” says Fraser. “The tools are there — it isn’t a computer science problem, it’s a political science problem.”

(Kelly Wilkinson/IndyStar/TNS)

A Broader View of Data

Years of disinvestment in public health infrastructure have led to an uneven patchwork of technology capabilities, but now that these vulnerabilities are in the open, Christopher sees an opportunity to reconsider both technology infrastructure and the nature of the information that is being collected.

“Equity is not going to be achieved if we don’t shift to some degree what we are measuring and perhaps most importantly, if we don’t engage authentic community voices in helping us to find out what should be measured,” she says.

Christopher is the director of the National Commission to Transform Public Health Data Systems, which developed recommendations for incorporating metrics in public health data systems that reflect social determinants of health.

New data visualization tools make it possible to interpret information in ways that were previously not possible. When platforms are compatible, data can be shared with great speed. Bringing more and more of these capabilities to public health involves collaboration with the private sector.

The exhaustion that public health workers are experiencing could be enough to explain their relative lack of enthusiasm about technology innovation. “There’s some work to be done to support frontline workers and to be responsive to the unprecedented experience that we’ve all lived through and are in,” says Christopher.

Not a Technology Problem

Public health has a long way to go to match the technology behind billion-dollar websites that the public uses daily to buy plane tickets or order goods from online retailers, says Fraser. “We still have states that can’t collect data electronically from the health-care side of the house.”

Christopher believes the private sector recognizes the importance of helping close this gap. A number of companies developed apps intended to support contact tracing, for example, though in the U.S. they ran afoul of privacy laws, personal comfort zones and skepticism about public health efforts.

“Our data system is a monument to the tower of Babel,” says Castrucci. “This is not a technology issue — we put a robot on Mars and it went out and took pictures. It’s about privacy and political will and we know how hard it is to overcome those issues.”

Related Articles