In Brief:

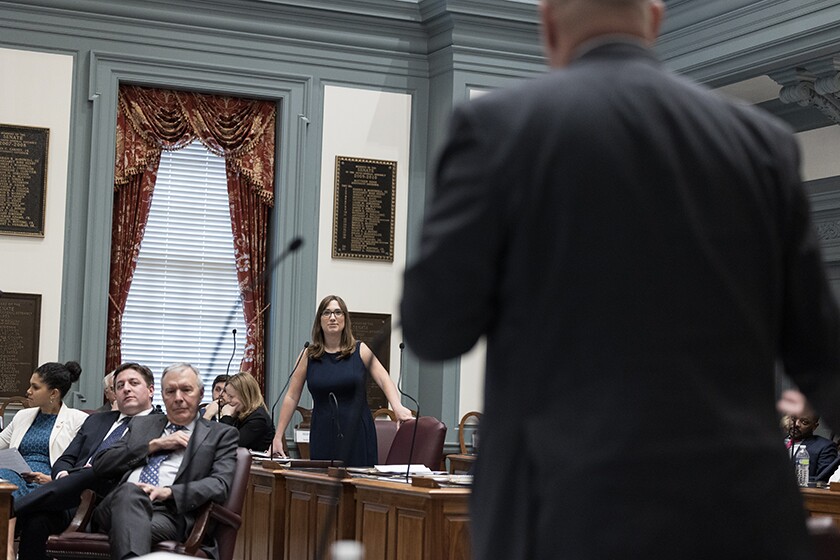

Sarah McBride rises to speak on the Senate floor in the state capitol in Dover, Del. Late in the afternoon on this winter’s day, the Democratic legislator is sponsoring two resolutions. The first is in recognition of Holocaust Remembrance Day and passes unanimously among the 20 senators present. The second is in support of statehood for the District of Columbia, an unpopular position among the six-member Republican minority.

When Sarah finishes making her case in support of statehood, the debate takes on a scholarly tone as the Federalist Papers are cited numerous times, on both sides of the aisle. The resolution ultimately passes, with only Democratic votes. Having clearly enjoyed the high-level back-and-forth as much as her victory, Sarah makes an immediate beeline to her Republican colleagues, and with a smile says, “Wasn’t that fun?”

With the colonial revival interior of the Senate chamber as a backdrop, and excepting the members’ dress, the scene could have taken place two centuries earlier. But times have changed. Sarah McBride is just starting her second term as one of the country’s few transgender state legislators, and the first senator in Delaware or any other state. Her election in 2019 drew a swarm of national news media to this small capitol. But her status as a state senator, on this day at least, seems nothing but ordinary.

Times may have changed, but Sen. McBride is cognizant of the role she continues to play. “I don't think in my lifetime we will get to a point where [being a trans elected official] is so commonplace that it's not noteworthy,” she says. “It is noteworthy. It is new, to have trans people in these types of positions. It is important for trans people, myself included, to see examples of ourselves in politics and business and art throughout society.”

While the state’s size and neighborliness helped Sarah succeed, a bigger factor was her district’s Democratic tilt. She won her first race with over 70 percent of the vote, aligning with totals racked up by a Democratic president and governor. Two years later she ran again, this time unopposed.

Born 32 years ago in Wilmington, Sarah had an unusually early interest in government and politics. Franklin Roosevelt was her favorite. Before she was a teenager, Sarah would get to meet a future president up close.

One day in February of 2002, Sen. Joe Biden and his wife Jill strode into a Wilmington pizza shop and made their way to the table next to 10-year-old Sarah, who was having dinner with her mother and father. “My parents very politely interrupted Joe as he was coming in and introduced me. The only reason they did was because of just how obsessed and interested I was.” Sen. Biden kneeled down, ripped a page from his briefing book, and signed his name under “Remember me when you are president.” The daily schedule page was immediately hung on her bedroom wall, next to a collection of Little League trophies.

Delaware Treasurer Jack Markell met 13-year-old Sarah at the state Democratic convention in 2004. Their paths crossed several more times over the course of the campaign season. Two years later Sarah’s parents hosted a small campaign event for Markell in their Wilmington home where Sarah was tasked with introducing the candidate. That went well enough that Markell asked the 16-year-old to introduce him again, this time at his official announcement for re-election as treasurer. What followed was a three-year stint opening at events for Markell as he successfully campaigned for treasurer and then governor. Following work as a campaign intern, Sarah’s first paid job was as a Markell field organizer in the area she now represents.

In 2009 Sarah left for Washington, D.C., to attend American University, where she served in the student senate as a sophomore and became student government president the following year. Home on break, she came out to her parents as transgender on Christmas Day 2011. Over the next few months, she limited the news to family and friends, including Gov. Markell, who vowed that nothing would change between them.

Andy Cray was a lawyer and LGBT rights advocate. He was also a transgender man. The marriage was short. Andy died of cancer just four days after their wedding. “It's the most life-changing experience I've ever had,” says Sarah. “I always talk about the most formative experience in my life. It's not being trans. It was being Andy’s spouse and being his caregiver during his battle with cancer.”

After Andy’s passing, Sarah was anxious to return to Delaware, but wary of living in a place that still lacked nondiscrimination protections based on gender identity. Resolving to change the law in her home state, she joined Equality Delaware, the state’s primary LGBTQ advocacy organization, and focused her efforts on passage of marriage equality and gender identity protections in the 2013 legislative session. Having recently been re-elected, Gov. Markell let Sarah know he would support both measures.

Now on her own, Sarah was traveling a lot for the Human Rights Campaign, an LGBTQ advocacy group. Meanwhile, in 2017, Danica Roem was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates, making her the first openly transgender state legislator in the country. “It was such a clear example that trans people could run and win,” Sarah says. “And then in 2018, more trans people got elected to state houses across the country, a further validation that Danica’s win wasn't an exception.” Inspired by Danica’s success, Sarah announced her intention to run for Delaware state senator in July 2019.

Sarah built her campaign around the issue of paid family and medical leave, a passion reinforced by her experience caring for Andy. “But also so that people would have something in their mind about me that wasn't just my gender identity, as proud as I am of that,” she says. “I wanted them to have another reference point.”

Rep. Mike Smith is one of 15 Republicans in the 41-member Delaware House. Describing himself as a “champion for small business,” he credits Sarah with making a concerted effort to address his concerns before voting on the final bill. “Sarah didn’t need any Republican votes,” he says. “But she still worked her butt off to make sure that there was something bipartisan that we could work with. We were able to get multiple Republican votes because of that.”

While Sarah’s gender identity could be seen as a liability, she used the resulting onslaught of media attention to her advantage. “I had a unique platform that was a byproduct of my identity,” she says. “And that was a benefit that legislators don't typically have when they first get elected.”

A small plastic toy of clattering teeth, a recent gift from a colleague, is prominently displayed on her office shelf. “It’s so me,” says Sarah, picking it up. “The only way it could be more me is if you wind it up and it never stops talking.”

“I think that people have been able to see who I am,” she says. “I didn't run to be the trans senator. And I haven't been the trans senator. I am a senator who is trans.”

As a small blue state, Delaware may have been the best place for a trans candidate to run and win. “I have been very fortunate,” Sarah says. “Because I have heard from transgender colleagues in other states where it's a controversy. People won't refer to them as gentle lady or madam chair. That has never been an issue for me. I certainly get my fair share of [hate] emails and voicemails. But they're not from constituents. They're from random people who think they're clever or want to be mean.”

With a real record of legislative success under her belt, and a smile on her face, Sarah makes light of her past and present experience. “I spent almost 10 years going into a room where people hated me because of who I am,” she says. “It is a breath of fresh air to go into a room where people hate me because of my policy.”

Related Articles