Republicans already hold 28 of the nation’s 50 governorships and history suggests that Democrats are bound to slip some more this year. Since World War II, the president’s party has lost four governor seats on average per midterm. Last November, Republican Glenn Youngkin was elected governor in Virginia, while Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy narrowly survived in New Jersey. “The most vulnerable incumbent governors are all on the Democratic side,” says Joanna Rodriguez, deputy communications director for the RGA.

It’s difficult to knock off incumbents, however. In recent midterms, usually just one or two governors have lost their jobs in general elections. While acknowledging that her party faces “headwinds” due to the midterm environment, Christina Amestoy, deputy communications director of the Democratic Governors Association, argues her members will be able to make a strong case on issues such as education and health care, adding that flush state budgets are allowing them both to cut taxes and cut ribbons at construction projects.

Although voters rarely split tickets for Congress, they remain more willing to tune out national issues and vote for governors based on state-specific questions. There are currently 10 states that voted one way for president in 2020 but have a governor from the other party in office. “When people look at who they’re voting for, for governor, I believe voters understand that a governor has the ability to make day-to-day changes in their lives in a way that congressional or Senate candidates or even the president can’t,” Amestoy says. “And so I think they expect to hear about those day-to-day issues on a more regular basis than they do from any of the federal candidates.”

The two states that at this point look most likely to flip are currently held by Republicans. Charlie Baker of Massachusetts and Larry Hogan of Maryland, who have consistently enjoyed among the highest approval ratings in the country, are both stepping down, creating great opportunities for Democrats in those crystal-blue states. Republican governors are also facing more contested primaries than Democrats. (We’ll look at those dynamics in an upcoming story.)

But Republicans will be going on offense in many more states. The Democratic Governors Association likes to brag it hasn’t lost an incumbent race since 2014, but that streak is bound to be snapped this year.

Minnesota Democratic Gov. Tim Walz has to worry not only about his future Republican opponent but a candidate from the Forward Party, founded by erstwhile presidential and New York mayoral candidate Andrew Yang, potentially siphoning off support. In Maine, former GOP Gov. Paul LePage is seeking to make a comeback against incumbent Democrat Janet Mills.

Republicans also think they can regain ground in the Southwest, targeting Michelle Lujan Grisham of New Mexico and Steve Sisolak of Nevada. Last week, the RGA announced it has reserved $8 million worth of airtime in the Las Vegas and Reno media markets for the fall. “Every poll shows Sisolak is vulnerable, as any COVID-era governor would be, but especially in a state so dependent on tourism during a pandemic,” says Jon Ralston, editor of the Nevada Independent, a news and opinion website. “His numbers are not great, but not awful and he has a ton of cash on hand.”

There’s broad agreement, however, that the most vulnerable Democratic governors are in Kansas, Wisconsin and Michigan. Here’s an overview of those races:

Kelly’s Chances in Kansas

A lot had to break right for Laura Kelly to get elected in Kansas in 2018. After Sam Brownback became an ambassador, his replacement, Jeff Colyer, lost the GOP primary by 393 votes to Kris Kobach, who had long been a controversial figure due to his hardline stances on immigration and voting. Kobach then ran a poor campaign and Kelly still ended up winning only by a plurality.

“Laura Kelly can essentially kiss being governor goodbye by the end of the year,” Rodriguez says.

In 2020, President Donald Trump carried Kansas by 14 points. Republicans hold supermajorities in both legislative chambers and the state hasn’t elected a Democrat to the U.S. Senate in nearly a century. The party has united behind state Attorney General Derek Schmidt, who is certainly a conservative but comes across as more mainstream and statesmanlike than Kobach. “Her biggest weakness is that she is in Kansas,” says Bob Beatty, who chairs the political science department at Washburn University. “It’s just sheer party registration.”

(Mark Reinstein/Zuma Press/TNS)

Although Kansas is a Republican state, Democrats have served as governor for 32 of the last 56 years. The Kansas GOP has long been divided between distinct conservative and moderate wings. Some of the moderates have become Democrats, but many remain in the GOP and are willing to support the occasional Democrat. Kelly enjoyed support from some high-profile Republicans four years ago and she recently released a list of 60 Republicans who support her, including several former legislators.

“I don’t know what Laura Kelly’s magic elixir is to stay popular in a red state,” Smith says. “She goes easy on the culture war stuff and says we’re Kansans, we do things our own way.”

Narrow Winner Seeks Second Term

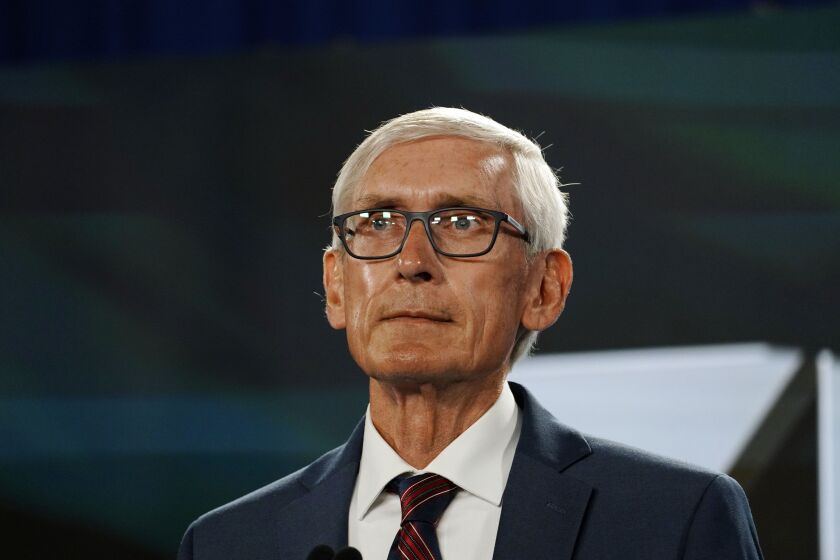

Democrat Tony Evers unseated Wisconsin GOP Gov. Scott Walker in 2018 by a single percentage point. The GOP-dominated Legislature immediately moved to strip the governor’s office of certain powers in a lame-duck session. Evers and legislative leaders have never gotten along since. They go for months at a time without talking. The Wisconsin Legislature, nominally a full-time body, has already gone home for the year and has already blown off Evers’ call for a special session to deal with the state surplus. That type of inaction has become routine.

Almost the only time Evers and legislators interact is when he sends them a veto message, which happens all the time. But Evers’ decision not to veto a bill last year has buoyed his re-election chances. The governor said he had no choice but to accept the Legislature’s budget or risk losing out on billions in federal COVID-19 aid. He then quickly claimed credit for more than $3 billion worth of tax cuts.

“When he signed the budget, it included nothing he’d asked for and everyone was girding for a fight,” says Mordecai Lee, a political scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. “Instead, to everybody’s surprise, he signed it and took credit for the tax cut. He said he was proud to sign it and he was always for tax cuts.”

Republicans find this unconvincing, noting that Evers has proposed plenty of tax increases, while his own budget proposal included items they think won’t fly outside the Democratic base on issues such as environmental restrictions. But it’s hard to get voters all that worked up about things that didn’t actually happen. That’s why, perversely, Republican legislators may have done Evers a political favor by successfullychallengingmuch of his authority to order lockdowns and mandates during the pandemic. “I think right now, Gov. Evers is actually in a pretty good position,” says Democratic state Sen. Jon Erpenbach. “We came through the pandemic pretty well, things are going well in terms of the economy and financially, the state’s swimming in money right now.”

(Melina Mara/Getty Images/TNS)

Where once Kleefisch acknowledged Biden as the winner of that election, lately she refuses to say one way or the other. The race has already turned nasty, with Nicholson attacking Kleefisch and Kleefisch in turn calling Nicholson an “opportunist” and a “shape-shifter.” Kleefisch clearly has the better organization, but she’s also going to be seen as the establishment candidate. An August primary date gives the eventual nominee relatively little time to mend fences. “It is definitely trending toward a more divisive and contentious primary,” says Andrew Hitt, a Republican strategist and former state party chair.

For all that, there’s no question that the eventual Republican nominee could beat Evers, who after all barely won four years ago in a much better environment for his party. Evers is very much touting himself as a brake on Republican excess and a defender of democracy.

“While I think he’s vulnerable, I don’t think there’s anything to suggest that this isn’t going to be a very close race,” Hitt says. “It’s a toss-up right now.”

Failure to Fix the Damn Roads

Gretchen Whitmer has to decide how she feels about gas taxes. Last week, the GOP-controlled Michigan House passed a six-month suspension of the state’s 27-cent per gallon gas tax. The state Senate will follow suit this week. House passage came just a day after Whitmer joined other Democratic governors in calling for a suspension of the federal gas tax.

Whitmer, who ran four years ago on the slogan “fix the damn roads” and called for a 45-cent gas tax increase during her first year in office, doesn’t seem thrilled with the idea of suspending the state tax. A six-month suspension would cost the state $725 million. Republicans intend to call her out on it. “Why in the world would we write a letter to Congress asking for lower gas prices somehow, someday when we can just step up and fix it ourselves,” state House Speaker Jason Wentworth said in a statement.

Having failed to raise gas taxes early in her term, Whitmer had the unilateral authority to create a $3.5 billion bonding program. That money, combined with federal infrastructure dollars, means more asphalt on the ground. But it’s hardly a fulfillment of her pledge to address decades of neglect.

“She’s going to be hit for sure on not fixing the damn roads,” says Zach Gorchow, executive editor and publisher of Gongwer Michigan, a news service. “There will be a lot more construction than people have seen in recent years and that helps blunt it, but the governor would admit she has not come up with a long-term solution to fix the roads.”

Whitmer also opposes a $2.5 billion income tax cut approved by the Legislature, calling it fiscally irresponsible. She prefers a more modest cut to pension and retirement income taxes. But she’ll claim credit for an auto insurance overhaul that’s leading to $400 rebate checks going out just now. She also shifted her stance regarding COVID-19. Whitmer was among the more aggressive governors early on in the pandemic, but lifted essentially all restrictions by last summer.

Whitmer’s greatest strength may be the lack of a formidable opponent. Plenty of people are running but unlike in Kansas and Wisconsin, Michigan Republicans were unable to recruit a statewide official to run against her. The leading candidate may be James Craig, a former Detroit police chief. Polls show Whitmer running ahead of Craig, although her support is below 50 percent, which is not a great place to be as an incumbent.

But incumbent governors rarely lose in Michigan. Since the state switched to four-year terms more than a half-century ago, only Democrat James Blanchard was defeated while seeking a third term in 1990. “She won’t have nearly the favorable environment she had in 2018 and her team knows that,” Gorchow says. Still, he adds, “Right now, she’s a slight favorite to win a second term.”