The city is still in the top five in the 2021 survey, with a surplus equivalent to $3,000 per citizen after all its bills are paid. In 2013, Detroit replaced Stockton as the largest city to seek bankruptcy protection, emerging in 2014. But it has not managed a similar resurgence.

Motor City currently has a “taxpayer burden” of $6,100 — the sum each citizen would have to pay to bring its bills current. It is ranked among “Sinkhole Cities” by Truth in Accounting.

Stockton deserves high praise for the hard decisions and sacrifices that made its recovery possible, says its new city manager, Harry Black, but it’s time for the “muscle memory” that remains from austerity measures to be replaced by a spirit of growth.

“The bankruptcy scared the city straight, which is what you want it to do, but not at the expense of growth and innovation,” says Black. “Now we’ve got to focus on catching up to the 21st century.”

(Calixitro Romias/The Stockton Record/TNS)

Cultural Shift

Black brings public- and private-sector experience to his new post. He served as Baltimore's chief financial officer, where he helped the city achieve a AA bond rating. Before coming to Stockton, he was Cincinnati’s city manager.

Black’s tenure in Cincinnati began in 2014. There, he established an Office of Performance and Data Analytics (OPDA) to bring a performance-managed approach to city government. This work included the creation of a data portal where citizens and government officials could access information to follow progress toward the city’s program goals, and an Innovation Lab (iLab) to identify barriers to efficiency and generate new approaches to government processes.

“None of this is particularly novel in the private sector,” Harvard law professor Susan Crawford wrote at the time about Black’s efforts. “But it’s a cultural shift to see a city in this way.” At the end of its second year, the OPDA reported that it had saved the city $3.3 million.

While this approach to management could benefit every city in America, it has particular value for Stockton. The city "is in catch-up mode — it lost five to seven years because of the bankruptcy,” he says. “This integrated approach allows it to overcome the ways that it's fallen behind in terms of 21st century public-sector practices.”

City of Stockton

The Future, On One Page

As of May, Stockton has its own OPDA, led by the former manager of the city’s IT department, Katie Regan. She has been gathering data from many sources.

“It's been an incredible kind of network and building and collaborative experience across our departments, which I'm just so grateful for,” she says. “Depending on the topic, we have at least two fiscal years of history, but in some cases we are doing what we can to pull an even deeper history.”

Collection, organization and analysis of data occurs in coordination with another tool that Black has brought from the private sector, the One-Page Strategic Plan (OGSP©), which summarizes priority goals, strategies, plans and metrics.

While in Cincinnati, Black struck up a friendship with Harry Kangis, a former Procter and Gamble executive who co-founded the nonprofit One Page Solutions. Kangis mentored Black as he developed an OGSP for Cincinnati. (Stockton’s 2020-2021 OGSP can be seen here.)

“I don't think there's any other local government that is doing this,” says Black. “It’s a clean, efficient way to look at how we transition from council goals to action.”

The metrics on the OGSP give a high-level view of how progress can be measured, but they are just part of the data that Regan’s office collects. Hundreds of other data points are in a performance scorecard that includes factors that contribute to attainment of large targets such as reduced crime rate.

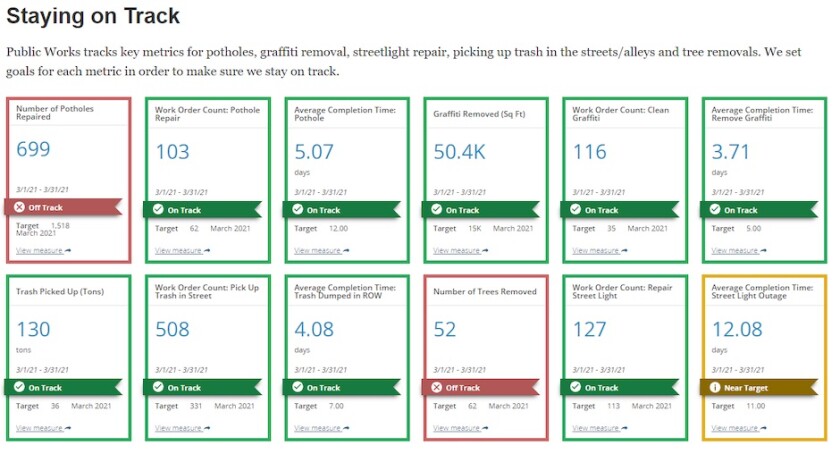

High-level goals may take time to achieve. The StocktonStat portal, scheduled for launch on June 30, will include data on the number of potholes and streetlights repaired, or square feet of graffiti removed, says Regan. “The stat process, and this shared data, are part of a continuous conversation and relentless follow up toward our performance targets.”

(City of Stockton)

A Laundry List of Actions

Due to the pandemic, the first meeting of the Stockton iLab took place online. It looked at the city’s development services and permitting process. Historically, this has involved multiple handoffs and cross-department review, making it a perfect candidate for process review, says Regan.

The meeting resulted in a laundry list of action items necessary to realize improvements. They included leveraging data to establish a performance baseline against which progress could be measured — e.g., how many hands a permit passes through for a given project and how long it takes to complete permit approval.

iLab recommendations also included cross-training counter staff, so they don’t need to refer customers to someone else. The action log from the iLab meeting was transitioned into the stat process, to guide city departments through the completion of actions necessary to improve permitting services.

“The relationship can go both directions,” says Regan. “The iLab can be the raw material that feeds into stat, or we can go into the iLab from stat work.”

(Eduardo Contreras/The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Evidence Matters

The pandemic forced two reckonings, says Kristine Goodwin, director of NCSL's Center on Evidence-Based Policymaking. Early on, the public sector had to channel abruptly limited resources to the most effective programs. As funds from the American Rescue Plan became available, the challenge shifted to finding the best uses for a sudden and historic abundance of resource.

“We’ve seen strong interest from states in using data to drive budget and policy decisions,” she says. “Why not invest in programs that are proven to work?”

San Diego County, one of the most populous in the nation, is among the jurisdictions that, like Stockton, have recently made formal commitments to data-driven decisions. In May, the San Diego Board of Supervisors approved an investment of $3.5 million to launch a comprehensive approach to evidence-based policymaking and establish an office of evaluation, performance and analytics.

The county has 42 offices and a $7 billion budget, says Jeffrey Yuen, senior adviser to San Diego County Supervisor Terra Lawson-Remer. The new office couldn’t be expected to track everything from its inception.

“We need to be strategic, to focus on the things that are going to be important for this county in the next three to five years, collecting data and evidence in those spaces,” says Yuen. These include climate and sustainability; San Diego County has set a goal of zero carbon emissions by 2035, the first in the nation to make such a commitment.

Supervisor Lawson-Remer, the author of the proposal approved by the San Diego Board of Supervisors, has experience balancing policy and economy. She served as an economist with the United Nations and the World Bank, and as a senior adviser to the U.S. Treasury Department during the Obama administration.

“Evidence matters in public policymaking,” she told the board. “By highlighting what is working and what is not, evidence can guide and inform significant policy and budget decisions to be more effective, more equitable and more focused on delivering the best outcomes for all San Diegans.”

A Collaborative Ecosystem

Two-thirds of government workers consider public service to be a “career,” a view shared by less than half of those who work in the private sector. A work culture built on data collection, and performance management based on real-world metrics might be expected to be fraught with stress. But that doesn’t seem to be the case for those who took a job to make a difference.

Rather, Black has found that a performance-oriented system empowers public-sector workers, enabling them to deliver on strategic goals and building their confidence. “It creates a collegial, collaborative working ecosystem for city employees,” he says. “It does wonders for morale, re-energizes employees and makes them want to pursue excellence.”

Katie Regan expects StocktonStat to have a similar impact on citizens. A myriad data sets will be accompanied by a visualization dashboard that they can explore to learn exactly what their government is doing.

“They’ll be able to play around, point and click, become more informed and educated,” she says. “Hopefully, as a result, they’ll be better equipped to participate in the whole governance process.”