Voters in seven states — including deep-red Missouri and Montana — chose to protect or expand access to abortion through ballot initiatives.

“This won’t be the last time Missourians vote on so-called ‘reproductive rights,’” Missouri Republican state Sen. Mary Elizabeth Coleman, who opposed the ballot measure, wrote in a press release. “I will do everything in my power to ensure that vote happens.”

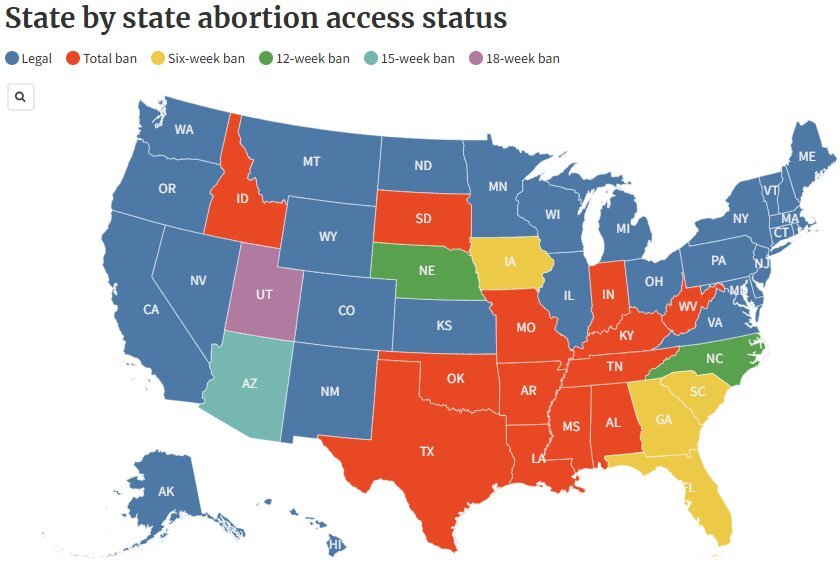

In Missouri and Arizona, the ballot measures will expand abortion access beyond what state laws currently allow. Though those constitutional amendments are set to go into effect in the coming weeks, abortion is unlikely to become immediately accessible in those states because abortion-rights advocates will have to go to court to overturn existing laws.

In addition, anti-abortion groups and their legislative allies in recent years have worked to undermine abortion protections through laws and court challenges based on concepts such as fetal personhood, parental rights and fetal viability. Those efforts could limit the impact of the new ballot measures.

Supporters of the Missouri measure anticipate continued opposition. Mallory Schwartz, the executive director of Abortion Action Missouri, told a crowd celebrating on election night that “anti-abortion, anti-democracy politicians are going to try to stomp us out,” according to the Missouri Independent.

“They’re going to try to fight us in court, and they’re going to file new attacks in Jefferson City,” Schwartz said.

Some abortion-rights supporters worry that without a federal constitutional right to abortion, which the U.S. Supreme Court struck down in its 2022 Dobbs ruling, the new state-level protections are vulnerable to federal moves that could override them.

After the Dobbs decision, the Biden administration took several steps to protect access to birth control, abortion medication and emergency abortion care at hospitals.

But Nourbese Flint, president of the abortion-rights group All* In Action Fund, said the incoming Trump administration could restrict access even in states that have abortion-rights measures on the books.

Source: States Newsroom • Last Updated: 10/07/2024

“Unfortunately, we are in a position where even if your state has passed great legislation, the actual, tangible access to medication abortion might be harder” in the future, Flint said.

Some anti-abortion groups want the Trump administration to enforce the Comstock Act, a long-dormant 1873 law they believe could be used to make it a federal crime to send or receive abortion pills in the mail.

The Trump administration also could reverse a current policy under the federal Food and Drug Administration that allows the mailing of abortion medication. And when the U.S. Supreme Court dismissed a case earlier this year involving FDA regulation of the abortion medication mifepristone, it left the door open for future challenges. Meanwhile, some states have laws limiting access, such as requiring in-person physician visits for abortion medication, effectively barring patients from accessing it via telemedicine.

“I don’t want people to think just because they voted ‘yes’ to protect reproductive rights there is going to be a magic wand to restore those rights,” said Chris Melody Fields Figueredo, executive director of the Ballot Initiative Strategy Center, which supports progressive ballot initiatives nationwide.

“They’re going to have to double down and fight to make sure people are going to receive the reproductive care they need and deserve.”

In addition to reliably red Missouri and Montana, voters on Tuesday also approved abortion-rights measures in presidential battlegrounds Arizona and Nevada and solidly blue Colorado, Maryland and New York. In Nevada, voters will have to approve the amendment again in 2026 for it to go into effect.

Before last week, voters in six states — including conservative Kansas and Kentucky — had endorsed abortion rights when presented with abortion-related ballot questions.

But Tuesday’s election marked the first time since the fall of Roe v. Wade that abortion-rights ballot measures failed: Voters defeated proposed amendments in Nebraska and South Dakota. And in Florida, 57 percent of voters supported an abortion-rights amendment, but it fell short of the 60 percent supermajority required for passage.

Questioning Viability

The ballot measures in Arizona, Missouri and Montana establish the right to abortion up to “fetal viability.” It’s a term that lacks an exact medical or legal definition, and thanks to medical advances over the years, viability has moved earlier in pregnancy. Today, it’s generally considered to be around 23 or 24 weeks of pregnancy.

“‘Fetal viability’ is not a legal term,” said Dale Margolin Cecka, director of the Family Violence Litigation Clinic at Albany Law School and a former Georgia assistant attorney general. “Even in states that now have amended their constitutions [to permit abortion], I can foresee challenges to the ‘fetal viability’ aspect of those amendments.”

For example, she said, state legislators could attempt to restrict abortions by defining “fetal viability” in state law in such a way that might create doubt in the minds of providers about whether a patient’s pregnancy meets state requirements for a legal abortion.

In the days leading up to the election, Florida Attorney General Ashley Moody, a Republican, used the vagueness of the “viability” standard in Florida’s proposed abortion amendment to ask the state’s highest court to keep the measure off the ballot, though the court declined to do so.

In Montana, where abortion was already legal until fetal viability under a 1999 state Supreme Court ruling, the new constitutional amendment shores up that protection by defining fetal viability. The amendment says viability should be based on “the good faith judgment of a treating health care professional and based on the particular facts of the case.”

‘Personhood’ and Parental Rights

The concept of “fetal personhood” also could be used to circumvent state constitutional amendments on abortion. Long a cornerstone of the anti-abortion movement, fetal personhood is the idea that a fetus, embryo or fertilized egg has the same legal rights as a person who has been born. If state law considers fetuses to be people, the thinking goes, the abortion would be considered murder.

Missouri state Rep. Brian Seitz, a Republican, told Stateline in July that he plans to introduce a fetal personhood bill in the upcoming legislative session that would grant “unborn children” the same rights as newborns. His hope was that the bill could protect embryos and fetuses regardless of whether Missourians passed a constitutional amendment guaranteeing the right to abortion.

Cecka also expects to see state legislators continue testing abortion protections with so-called parental rights laws. Since Dobbs, conservative legislators in several states have filed parental consent bills to restrict access to abortion, birth control and other reproductive health care for people under age 18. Proponents argue such laws are needed to protect the rights of parents and to prevent other adults from persuading adolescents to get abortions.

The lawsuit filed last week by Missouri reproductive care providers to strike down several of Missouri’s abortion restriction laws after passage of the constitutional amendment does not challenge the state’s parental consent law.

In Cecka’s view, abortion access remains at risk, even in states that have passed protective laws, unless federal protections are put in place.

“In red states where there’s a strong enough push, the anti-reproductive freedom movement is a big machine with a deep bench, and they’re ready to fight,” she said.

Stateline is part of States Newsroom, a national nonprofit news organization focused on state policy. ©2024 States Newsroom.