The great philosopher Hank Williams Jr. expressed this best: “A Country Boy Can Survive.”

However, that’s more trope than truth.

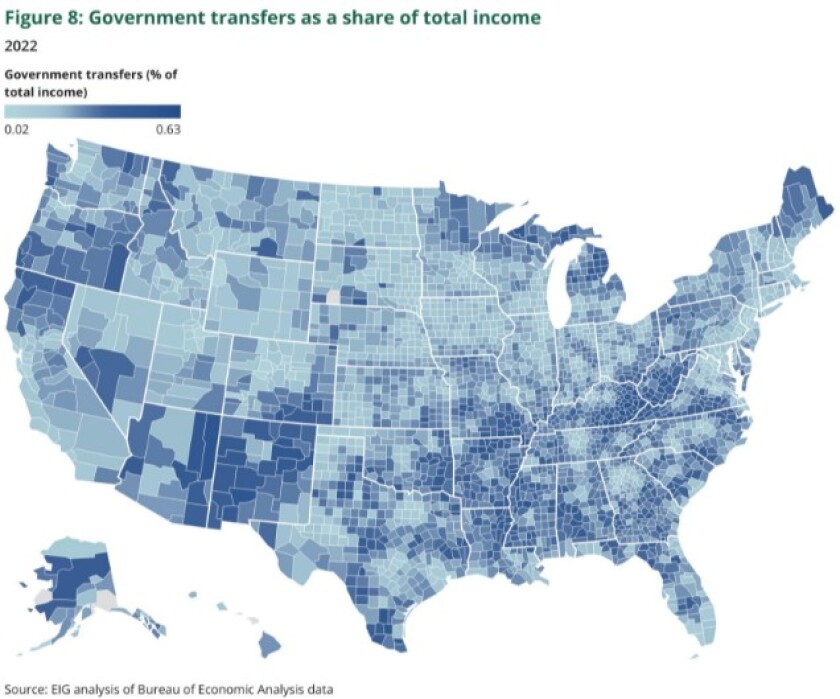

A recent study by the Economic Innovation Group — a D.C.-based think tank that describes itself as bipartisan — shows just how much rural America is dependent on government funding.

More specifically, the EIG study — “The Great Transfer-mation” — documents how Americans are increasingly reliant on checks from the government, and how those government-dependent Americans are concentrated in rural areas.

“Income from government transfers is the fastest-growing major component of Americans’ personal income,” the report begins. “Nationally, Americans received $3.8 trillion in government transfers in 2022, accounting for 18 percent of all personal income in the United States. That share has more than doubled since 1970.”

This isn’t a case of lazy, shiftless Americans milking the system so they can live on the dole, the classic tale of the “welfare queen.”

Rather, this is a simple result of Americans growing older, a demographic fact of life that we haven’t come to grips with yet politically.

Seven states — Alaska, Arizona, Kentucky, Mississippi, New Mexico, Texas and West Virginia — now have counties where government transfers represent a majority of the community’s personal income. The highest figures are in eastern Kentucky, where 60.86 percent of the personal income in Martin County and 63.17 percent in Owlsley County comes from the government in some ways.

In Virginia, the locality most dependent on government transfers is Dickenson County, where such payments account for 48.72 percent of the personal income in the county. As you can see on this map, the localities with the highest dependence on government transfers are rural localities, most especially in the coal counties of Southwest Virginia. The lowest figures are in Northern Virginia, where the figure drops to 5.42 percent in Arlington County and 5.71 percent in Loudoun County. (Arlington has the third-lowest share in the country; only San Mateo, Calif., and Midland, Texas, are lower at 5.3percent.)

Get the data • Created with Datawrapper

That's true, and it highlights some of the political disconnects here. However, it's also true that the real driver here is not political ideology but age (and to some extent, income, but especially age). The localities with the highest dependence on government transfers tend to be the oldest ones.

Get the data • Created with Datawrapper

As the nation ages, and birth rates fall, that gap will only widen.

This raises all sorts of political questions, of which the Axios headline highlights one: The voters who most strongly supported Trump are the ones who would most keenly feel the impact of one of his campaign promises, to slash government spending. Trump voters may not care if some six-figure government worker in Northern Virginia loses their job (although perhaps they should, since income taxes from Northern Virginia help subsidize rural schools, but I digress); what are they going to think if their Social Security check winds up on the chopping block?

Even Democrats, though, will be forced to confront the basic math. Here's some of that math:

“The share of the population ages 65 and over has risen from 9.8 percent in 1970 to 17.3 percent in 2022” — which means the share of the population most dependent on government transfers has nearly doubled.

“Economic downturns have accelerated the expansion of the transfer economy. Total transfer income has emerged permanently higher from each recession since at least the 1970s. The resulting stair-step pattern suggests that each downturn leaves a legacy of expanded safety net programs and participation in its wake.”

“Healthcare cost inflation directly feeds into key transfer programs, and medical costs have risen nearly twice as quickly as overall inflation over the past several decades. In real (inflation-adjusted) terms, total spending on Medicare and Medicaid has grown more than three times as quickly as total spending on Social Security. To put the growing fiscal strain into perspective: In 1990, Medicare spending was $7,000 for every person 65 and over; by 2022, it had more than doubled to $16,000 in real terms.” Medicare and Medicaid are really the main drivers of government transfer payments; they account for 46 percent of the spending, compared to 31 percent for Social Security. Social Security is usually what gets the political attention — remember when Al Gore vowed to protect Social Security “in a lockbox”? — but it's Medicare and Medicaid that get the attention of the accountants.

Here's how quickly our dependence on government transfers has risen:

Reducing these government transfers, which many people feel were promised them, may not be politically tenable. (Musk may be about to find this out.) Raising taxes may not be politically tenable, or even economically desirable, either. For one thing, “tax hikes and entitlement reform are ... not enough to solve the problem, either alone or together,” the report says. Both may be necessary, it says, but the only real solution is more economic growth that can generate the revenues to keep funding these government transfers.

Creating economic growth in rural areas is always a special challenge. Even creating it nationally — to the degree necessary to fund all these programs — is difficult, the report says.

Here's why: We don't have enough young adults. Between now and 2024, the over-65 population is projected to grow by 20 million, but the working-age population is expected to grow by just 6 million, the report says.

That's a problem — a huge problem — because we count on taxes paid by workers to cover the expenses of all those retirees.

“Not since the aftermath of World War II has the country been forced to confront such a troubling fiscal situation,” the report says. “In recent years the federal debt has returned to those all-time highs as a share of GDP — only it has happened through the normal course of business rather than the exigencies of war. ... In the immediate post-war period, favorable demographics could be counted on to grow the economy back to fiscal sustainability. No such tailwind exists today.”

The report gingerly mentions some solutions:

We need a higher birth rate: “To truly address the underlying challenge, a growth agenda must include a heavy focus on making it easier to start and sustain families,” it says. That is also much easier said than done. We can't legislate procreation, and legislating the things that might encourage more procreation — inexpensive child care, for instance — comes with a hefty price tag.

We need more immigration: That may be the most politically touchy subject of all. Trump vows to carry out “the largest deportation” in American history. If he limits that to gang members who are dealing fentanyl, that's a fine thing. However, most of the immigrants who are here without benefit of papers are employed — a study eight years ago estimated that 70 percent of unauthorized immigrants were employed. That's about 4.8 percent of the nation's workforce, according to the Pew Research Center. These are people who are paying taxes, one way or another. To support our current standard of living, we need to increase the number of workers, and the number of taxpayers, not reduce them.

More uncomfortable politics: Many of the counties with the highest dependence on government transfers are overwhelmingly white, yet those programs may ultimately depend on the U.S. increasing immigration, even though many of those immigrants may not be white. The author Ronald Brownstein has written frequently about this, calling it the “brown and gray” dilemma: “An older white coalition seeking to impose its vision of America on an increasingly diverse younger population — while also asking that younger [population] to fund their retirement thru payroll taxes for Social Security/Medicare.”

It's easy for politicians to claim to be “pro-family” without talking about the fiscal implications and easy to rail against illegal immigration without addressing the demographic and economic reasons we actually need more immigration. (More immigration is not incompatible with a more strictly controlled border, of course, but it's rare to find politicians who can make those distinctions. We can't have people just walking in willy-nilly, but we do need more people coming in somehow, particularly more young, working-age people.)

Those are the big questions in this report. Some smaller ones are what happens to communities where so much of the population is dependent on government transfers and not paychecks from an employer. Generally speaking, that stifles economic growth. Aging communities usually don't have a lot of economic growth. It's young adults starting families and buying or upgrading houses that drive spending, not older adults who are downsizing or spending money on medical bills.

It's hard enough for older, rural communities to generate economic growth, but the growing dependence on government transfers may make it harder, the report says. Promoting economic growth in a community might require, say, building more amenities designed to attract younger families. More playgrounds or better schools, for instance. However, how much political support will there be from an aging population that has no direct stake in those amenities?

Or as the report puts it: “Growth requires investment and risk-taking, two values that run counter to the inertia of increasing transfer dependence. The danger is that voters themselves demand that resources get diverted away from the very investments in growth that are needed to make the status quo sustainable.”

Welcome to the future, and, in many places, the future is now.

Dwayne Yancey is the founding editor of Cardinal News, from which this is republished. Read the original here.

Governing’s opinion columns reflect the views of their authors and not necessarily those of Governing’s editors or management.