Van Buren Township, less than 30 miles outside downtown Detroit, was already part of the great auto supply chain in the Upper Midwest, but now it’s playing a much larger role. In October, a company called Our Next Energy began production of lithium-ion phosphate battery cells, the first fruits of the company’s $1.6 billion investment in a gigantic factory in the township. A few weeks later, the company cut the ribbon at its new headquarters in nearby Novi.

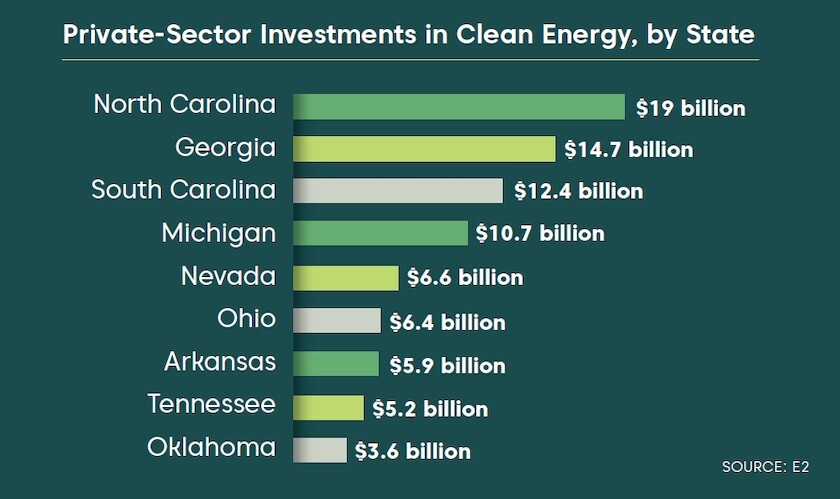

Other companies have come forward with plans to manufacture equipment for solar and hydrogen power in Michigan, as well as batteries and electric vehicles. These announcements add up to nearly $11 billion in new clean energy investment in the state prompted by passage in 2022 of the federal Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). That law offers both governments and private companies tax credits to help pay for clean energy projects.

The IRA has been celebrated as a turning point in America’s commitment to climate action, but the most revolutionary thing about it may be its power to promote growth. In this regard, it’s already exceeded expectations. To use an ironic metaphor, the IRA is proving to be rocket fuel for major investments in clean energy and manufacturing. Since the IRA was enacted in August 2022, an estimated 292 major new projects have been announced, representing almost $118 billion in private-sector investments. “The Inflation Reduction Act is an unprecedented economic development tool for this country,” says Aaron Brickman, of the climate nonprofit RMI.

More than half of the law’s $400 billion in support for clean energy, over 10 years, will come in the form of tax credits for companies that invest in clean energy, including manufacturing, clean fuel, electric vehicles, and power generation and storage. The law provides bonuses for companies that locate in lower-income communities, but the new money is a draw everywhere. The promised private-sector investments are on track to create roughly 100,000 new jobs. The only question now is whether the IRA will drive three or four times as much investment than was originally projected by the Congressional Budget Office, or only twice as much, says Brian Deese, a former director of the National Economic Council.

Officials in Michigan took careful steps to get ready, creating an infrastructure office that coordinates with various agencies to make sure they’re positioned to take advantage of federal grant opportunities. But the IRA’s tax incentives, to a large extent, sell themselves. States that lack any formal climate plan, or whose leaders deny that climate change is driven by human activity, are also landing major deals. Regardless of the politics, it should come as no surprise that red states including Georgia, South Carolina and Tennessee are among the leaders in attracting new projects, says Brickman, a former Commerce Department official, since they have been very good at economic development for decades.

Redwood Materials has announced plans to invest $3.5 billion to build a battery materials campus outside of Charleston, S.C. There, it will break down end-of-life batteries and use the metals reclaimed from them to create new anodes and cathodes (negative and positive terminals) for electric vehicle batteries. In announcing the facility, Nevada-based Redwood said that benefits from the IRA made it possible for them to make a bigger investment “at home” as well as opening the door to future exports. It’s the largest economic development announcement in South Carolina history, one that the CEO of Redwood Materials said made sense because of the state’s “commitment to creating a secure energy future.”

The fact that the law doesn’t pick winners on a partisan basis is a big strength, says Jack Conness, a policy analyst at Energy Innovation, a climate and energy think tank. “If you have an idea, if you have a company, if you have a product, come forward with it and receive federal funding to help revolutionize clean energy,” he says.

Some members of Congress have talked about repealing portions of the law, but the fact that it focuses on incentives, rather than regulation or enforcement, shifts the battleground out of politics and into the realm of business. Companies that are making long-term investments in power generation, manufacturing and transportation will push back hard if there are any serious changes to the terms of the deal.

This is the most amazing thing we’ve seen in the United States for a very long time.

David Burritt, CEO, U.S. Steel

Clean Energy's Promise

Clean energy is not just the future but very much part of the present. Over the next year, 92 percent of new generators nationwide will be powered by wind, solar and batteries, according to the Energy Information Administration. States — along with cities, counties, companies and even individuals — are getting in on the green gold rush. People used to consider themselves successful in the economic development arena if they helped close a single-billion-dollar capital investment project once or twice in a career, says Quentin Messer Jr., CEO of the Michigan Economic Development Corporation. Since the IRA announcement, he says, proposals from companies and site selectors are now coming in routinely in the $2 billion to $5 billion range.

No Republican in Congress voted for the Inflation Reduction Act. Nevertheless, about 70 percent of the manufacturing investment pledged to date is going to counties that supported Donald Trump in 2020, Conness says. Of the 10 states with the largest number of new clean energy projects, only California and New York are completely run by Democrats. Marjorie Taylor Greene, a Republican member of Congress from Georgia, has called climate change “a scam,” but her district is home to the largest solar panel manufacturing plant in the Western Hemisphere. Passage of the IRA prompted its Korean owner, Hanwha Q Cells, to announce it would invest $2.5 billion more in Georgia.

During his presidential run, Florida GOP Gov. Ron DeSantis pledged to increase fossil fuel production and fight electric vehicle mandates, but the White House estimates that the IRA could bring his state nearly $63 billion of private investment in solar energy generation and storage by 2030. IRA incentives were specifically called out by an executive at Polar Racking — a Canadian company that makes mounting systems, which keep solar panels pointed usefully toward the sun — which announced it was building a new facility in Florida last year at the same time it promised a new plant in Michigan.

When you think of Michigan, maybe you still picture car making. The time has come to associate the state with carbon reduction. In 2020, Michigan Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer set a target of economywide carbon neutrality for the state by 2050 and ordered the Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy to develop an action plan that could achieve it. The resulting MI Healthy Climate Plan set goals for renewable energy generation, electric vehicle adoption and building decarbonization, and emphasized economic development and job creation. Last year, with Democrats in control of Michigan’s government for the first time in four decades, the state passed a rush of climate legislation. A Clean Energy Future package set a target of 80 percent clean energy by 2035, required utilities to offer energy-efficiency programs and set labor standards for clean energy projects. In addition to setting broad policy goals, this bill, and several other new state laws taking aim at climate, addressed nuts and bolts such as streamlining siting for large-scale solar, wind and energy storage projects and establishing guidelines for permitting solar generation on farmland.

Infrastructure improvements in general have long been a primary goal for Whitmer, whose 2018 campaign was driven by the immortal slogan “Fix the Damn Roads.” The massive federal infrastructure law signed by President Biden in 2021 promised billions for this purpose for her state. She created the Michigan Infrastructure Office to coordinate action in response across multiple agencies. Generally speaking, states are set up to run programs that already exist, says Zachary Kolodin, the office’s first director. His job was to help departments respond to new opportunities presented by the infrastructure law. Kolodin’s office was up and running by the time the IRA was enacted, ready to align its historic climate funding with the state’s goals.

(Michigan Economic Development Corporation)

Administering for Results

The Infrastructure Office has taken up matters that otherwise would have fallen between the defined responsibilities of different state agencies, such as a competition for IRA funding to create six to 10 regional clean hydrogen hubs. Michigan joined with Illinois and Indiana to create a Midwestern hub that is set to receive up to $1 billion from the federal Department of Energy to produce hydrogen for power generation, refining, steel production and aviation fuel.

Kolodin’s technical assistance center keeps contractors on retainer to help state agencies with grant writing and can also fill gaps when local communities need help. In some cases, his office can provide the matching funds required by some federal programs. It can also draw on hundreds of millions of dollars Michigan has allocated to a competitiveness fund to complete the capital stack for a project.

Meanwhile, the Michigan Department of Labor and Economic Opportunity has been focusing on workforce issues. As a first step, it created a manual for relevant agencies to focus on the workforce development requirements that could come with federal dollars, highlighting existing elements of the state’s workforce development plan that could address them. Department officials then began meeting at least monthly with the state’s Department of Transportation and the Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy to help with the workforce components of their grant applications. “We work for them from beginning to end,” says Stephanie Beckhorn, deputy director of employment and training at the labor department. “When those dollars started coming in, we leveraged our existing workforce system and our registered apprentice system.”

Some of the billions coming to Michigan will be used to expand electric vehicle battery manufacturing. The labor department has created the EV Jobs Academy, a collaborative with 42 employers in the state’s automotive sector, including Ford and Toyota and automotive suppliers, to identify the skills and qualifications workers will need. The all-hands effort guides community colleges and universities in the development of curriculum and degree programs, which are reviewed by members of the collaborative. There are now 400 vetted courses, says Beckhorn. Employers have committed to interview individuals who have completed courses developed by the academy. A pilot scholarship program funded by the state awards $10,000 to college students hired to work at EV companies after completing their education, with support also available for paid internships.

The labor department views this work as a template for addressing other emerging needs. Michigan also aspires to be a leader in building a domestic semiconductor supply chain, a sector whose growth is also being stimulated by an incentive-driven federal program.

Finally, a Real Priority

When the federal Department of Energy was established back in 1977, “development and commercialization” of renewable energy was supposed to be one of its primary missions. That took a long time in coming. Passed 35 years later, the IRA is the strongest signal ever sent by the feds that such investments are vital. The way the law is set up, investment in clean energy infrastructure is outsourced. The tax incentives are rich, but they still require other actors to put up the cash.

Tennessee’s goal of becoming a leading supplier of lithium to the U.S. market took a big step forward when Piedmont Lithium announced plans to invest nearly $600 million in a plant in McMinn County. IRA incentives were a significant factor pointing to “robust” economics in a feasibility study Piedmont conducted for the project. Tennessee does not have a climate action plan but is one of several red states in a so-called Battery Belt of manufacturers working to meet demand for EV batteries.

Despite the flurry of such activity around the nation, incentives for state and local governments and businesses aren’t the only economic stimulus available under the IRA. The law allows billions of dollars in rebates for residential energy-efficiency projects and home electrification. These funds are expected to come available in 2024, though there’s been no announcement regarding a date. Only a handful of states have submitted applications for their programs. This is also the year when EV purchasers will get tax credits deducted from their vehicle purchase costs right at the time of sale.

There are reasons the IRA was supported solely by Democrats. Aside from the law’s cost, as well as other, unrelated provisions such as expanding tax enforcement that are anathema to the GOP, the clean energy money in the end is driven by concerns about climate. But as the amount of investment has already shown, clean energy is now living up to its long-hyped potential to create jobs. Globally, more people already work in clean energy than in fossil fuels.

The IRA is part of a U.S. manufacturing renaissance that’s well underway, the product of both enormous federal spending and the decisions companies are making to reshore facilities in response to pandemic-era breaks in the supply chain. No less an old industry mogul than David Burritt, the CEO of U.S. Steel, has called the IRA a spur to the return of domestic manufacturing. “This is the most amazing thing we’ve seen in the United States for a very long time,” Burritt said.