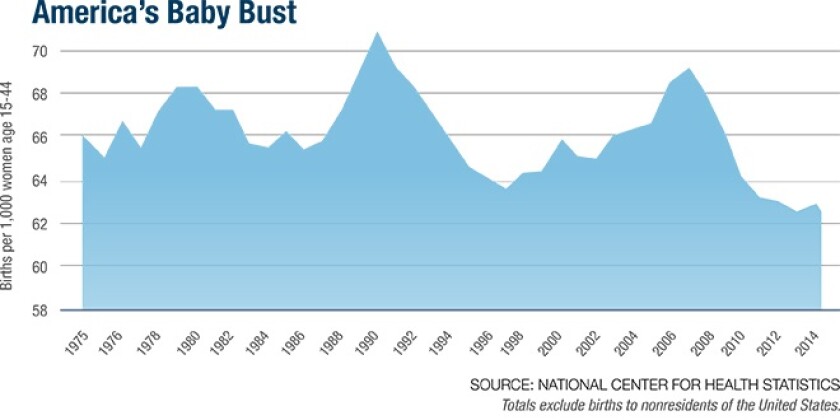

Newly-released federal estimates find that the fertility rate fell further last year to 62.0 births per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44, a historic low. In fact, 4 million fewer babies were born between 2008 and 2016 than would have been born had the rate continued at pre-recession levels, according to University of New Hampshire demographer Kenneth Johnson.

Over the long term, the baby bust could carry profound consequences for public policy if fertility rates don’t rebound. Classrooms could see more empty seats. Smaller workforces would likely reduce tax revenues. And demands for social services could shift.

Multiple factors have contributed to these low fertility rates. The first is the recession. Research has linked recession-era spikes in unemployment to corresponding decreases in a state’s fertility rate. Arizona -- whose economy suffered immensely with the bursting of the housing bubble -- has incurred the largest fertility rate decline of any state, a drop of 22 percent since 2007. Fewer births could compound matters in parts of the Northeast and Rust Belt where economies are struggling and populations have been declining for years. In contrast, North Dakota benefited from an oil boom and was the only state with a 2015 fertility rate above pre-recession levels.

Second, it’s well established that younger workers were hit particularly hard during the recession. Many of those who found jobs have been burdened with low wages or weighty student loan debts that make supporting children difficult. What’s more, many young adults who are more financially secure have chosen to delay marriage.

Another factor is immigration. Recent immigrants have among the highest fertility rates. If it were not for immigrant women, total annual U.S. births -- meaning the actual overall number of births, not the rate per capita -- would now be below levels reached in the late 1980s. But immigration gains from Mexico have halted, and states that have seen large numbers of immigrants in the past are now experiencing particularly sharp fertility declines.

The effects of reduced fertility won’t be clear for decades. But it’s possible to make a few educated guesses about them.

For starters, fewer workers in future years would likely cause tax bases to shrink. That poses serious problems, especially given the country’s aging demographics and the large segment of baby boomers already retiring. Consider Medicare: There were 3.1 taxpaying workers per Medicare recipient in 2015, a number projected to drop to 2.3 by 2030, according to the Medicare Board of Trustees.

Some speculate that a smaller workforce with less competition could benefit workers who wouldn’t otherwise secure better-paying jobs. But Chris Christopher, of the financial information firm IHS Markit, warns that such a scenario would be problematic. “It may be good for some individuals, but it would not be a good situation for the economy as a whole,” he says.

Just how much today’s low fertility rates actually reshape the future workforce will also depend on other factors. Economists believe immigrants could potentially offset the fewer births, and more women participating in the workforce would also help fill labor shortages.

Additionally, fewer babies would likely yield a more mobile workforce, since families with kids tend to buy homes and stay in place. Average household sizes have slowly shrunk over several decades, and a continuation would increase demand for housing units with fewer bedrooms.

One of the first effects of the fertility decline will be a drop in elementary school enrollment. The Maryland Department of Planning projects the state’s public elementary school population will decline each year until 2021, based on the lower number of births recorded in the past few years. Jurisdictions that aren’t adding residents via migration will need to rethink plans to build new or larger schools.

But lower birth rates do bring some good news. Falling rates of unintended pregnancy and far fewer births to teenage women are an important component of the declines. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, the teen birth rate has dropped 46 percent between 2007 and 2015. Rates have also dipped for women in their 20s, although not nearly as sharply. Meanwhile, birth rates for women in their 30s and early 40s have continued to climb, and are now at their highest levels since the 1960s.

Some population scholars say these trends hold a lot of promise. “Discouraging early childbearing and unintended childbearing has positive implications from everything to education to the workforce and parenting,” says Kristin Moore of Child Trends, a think tank studying children and families. Women in their late 20s and 30s are more economically stable than those in their teenage years, which should lessen the demand for social services. They’ll also likely maintain better health insurance, Moore says.

At this point, the biggest unknown is how many women are merely delaying childbirth and how many are forgoing it altogether. It’s reasonable to expect many who married in their late 20s and early 30s to have kids over the next few years, as recent gains in fertility for those in their 30s show. Although younger Americans have delayed marriage longer than prior generations, surveys suggest they’re still intent on having children. A Gallup poll found that views on the ideal number of children have changed little since the late 1970s.

Homeownership for young adults is also slowly rebounding, another sign that more young couples could be preparing to raise families. But the gains in births for older women haven’t been nearly enough to offset the declines among younger age brackets.

Only time will tell whether low fertility -- and all the policy implications that accompany it -- represents a temporary phenomenon or a more permanent feature of American society.

NOTE: This story has been updated to reflect new fertility rate data released June 30.