Nowadays, people are living longer than ever -- with diseases that Hippocrates could never have imagined -- and in circumstances in which a doctor could end their suffering. For more than a century, some American physicians have been arguing for a patient’s right to choose death, and for doctors to be able to assist in the process. The first bill allowing medically assisted suicide was introduced in Ohio in 1905. It failed, but academic papers and state legislation on right-to-die policies have been part of the medical landscape ever since.

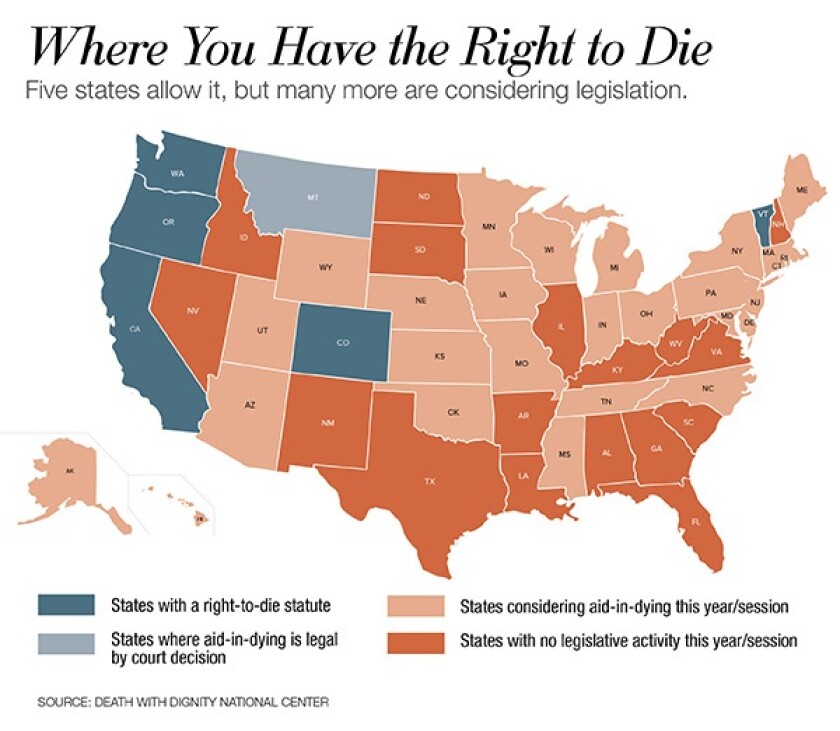

Oregon legalized aid-in-dying in 1997, far in advance of any other American jurisdiction. Washington state followed in 2008. Now the movement seems to be gathering momentum. In the past five years, California, Colorado, the District of Columbia and Vermont have all legalized physician-assisted suicide through legislation or ballot measure. Most have modeled their laws off Oregon’s. In order to obtain a prescription for a life-ending medication, two doctors have to determine a patient has no more than six months left to live and is mentally competent to ask for the medication. There is also usually a waiting period of 15 days between the first and second doctor’s approval before a medication is authorized.

For years after enactment of Oregon’s law, the practice was used very little. Only a few practitioners in the state openly employed it, and few residents were even aware it was available to them. Most hospitals remained opposed, and the Catholic Church was a strong presence in its opposition. But four years ago, physician-assisted suicide advocates launched a public service campaign throughout the state to raise the profile of the Oregon law and to change the policies of health institutions that didn’t support it. It worked. After a year of lobbying, all nonreligious hospitals in Oregon had dropped their opposition, and the number of medical practitioners offering aid-in-dying prescriptions had risen by 70 percent. It made other states take notice of the policy, says Kat West of Compassion and Choices, an advocacy organization that supports and tracks aid-in-dying legislation.

According to the Oregon Health Authority, a total of 1,749 state residents have taken their lives with a legal prescription since the law went into effect in 1997. In 2016, 133 ingested lethal medication. An overwhelming number of these patients were elderly (80 percent) and most had cancer (79 percent).

When the California Legislature enacted its law in 2015, Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown -- a former Catholic seminarian -- wrote, “I do not know what I would do if I were dying in prolonged and excruciating pain. I am certain, however, that it would be a comfort to be able to consider the options afforded by this bill. And I wouldn’t deny that right to others.”

On health care and social issues, California and Colorado tend to be trendsetters, providing a clue to what other progressive-leaning states will legalize or adopt. Now that aid-in-dying is legal in both places, it is plausible to imagine it as a normal part of hospice care in many parts of the country in the not-too-distant future. But will it happen? And should it?

Both proponents and opponents of allowing terminally ill patients to end their own lives believe more states will adopt the practice in the years to come. “I think it’ll expand before it contracts,” says Brian Callister, associate professor of medicine at the University of Nevada, Reno. Callister is an outspoken opponent of aid-in-dying laws, but he says that advocacy groups are well-enough funded to make the laws legal in more states.

His opposition to medically assisted suicide came about when he was transferring two patients to practices in California and Oregon. He says neither patient was terminal, but in both cases the company handling the insurance asked offhandedly if he’d thought about suggesting assisted suicide. “I was struck by how casual it was,” Callister says. “Those two cases made me sit up and take notice of end-of-life care.” (Medicaid covers physician-assisted suicide in both California and Oregon; Medicare and Veterans Affairs do not.)

A doctor’s guess on how long a patient will live following a diagnosis can never be exact -- the frequently used six-month standard is often arbitrary. But Callister argues that doctors are good at gauging when someone really is nearing the end. In those cases, he says, “better palliative care is the answer, not killing people.” Palliative care is a subset of hospice care that works to make a patient as comfortable as possible to ease the symptoms of an incurable disease.

The American College of Physicians (ACP), which has come out strongly against aid-in-dying, shares Callister’s sentiment. In a paper that appeared in the Annals of Internal Medicine in September, ACP President Jack Ende wrote that “the focus at the end of life should be on efforts to prevent or ease suffering and on the often unaddressed needs of patients and families. As a society, we need to work to improve hospice and palliative care, including awareness and access.”

For its part, the American Medical Association (AMA) directed its Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs to study the issue and its impact. Some AMA state chapters, however, have switched to a neutral stance.

Proponents of aid-in-dying argue that it isn’t just a way to hasten death. They think of it instead as an instrument in the toolbox for those who work in hospice care.

After all, “the will to live is the strongest drive we have,” says Neil Wenger, director of the Health Ethics Center at the University of California, Los Angeles. Wenger believes that since California’s law has gone into effect, conversations over end-of-life issues have improved -- more hospice patients want to talk about all of their options.

Thalia DeWolf is a clinical practice coordinator at Bay Area End of Life Options, a California organization that counsels people on end-of-life care and refers them to what it believes is the right treatment. She says the organization had to turn away patients in 2017 because it couldn’t keep up with the demand. Like Wenger, she believes that more people want to talk about end-of-life options as a result of the laws that have been passed. “We’ve had people say they want aid-in-dying, and then they went into hospice care and decided they liked that just fine -- and that’s great,” DeWolf says. “Most people in hospice care are comfortable. But this law is for those select people who don’t want a very painful last few weeks.”

David Grube, a retired physician who is chief medical officer at Compassion and Choices, says that Oregon’s aid-in-dying law is one reason the state has an A rating from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. “Just having that option is palliative,” he says. “By knowing that it’s there, people suffer less.”

But access to aid in dying often depends on where someone lives even in a state that’s legalized it. Religious and rural health organizations tend not to offer it. Grube says there are areas of Oregon with only Catholic health organizations, so residents there have to travel if they want to speak to a doctor about an aid-in-dying option. Other religious denominations are equally strong opponents. Church-affiliated hospitals make up 13 percent of California’s health system, and all have opted out of using the right-to-die law.

In the first six months after the law’s enactment in California, 111 people chose to take advantage of it, and the statistics were similar to those in Oregon: 87 percent of the patients were older than 60, and 59 percent had cancer. Data from Colorado’s first year of implementation in 2017 found that roughly 50 residents requested aid-in-dying drugs. About 30 hospitals across the state declined to participate in the program. The majority of them were church-affiliated.

New Jersey seems likely to be the next state to legalize the practice. Legislation passed the House in 2017, but went no further after Gov. Chris Christie promised to veto it. Supporters are likely to have better luck with the state’s new Democratic governor, Phil Murphy, although he hasn’t said publicly if he supports the policy.

Advocates acknowledge that right-to-die laws are not going to spread to every state, and even some of the more progressive states continue to encounter strong opposition. Last year, the New York Court of Appeals upheld a state prohibition against allowing doctors to dispense lethal medication to terminally ill patients. Five such patients filed a lawsuit asking the state to reconsider the prohibition, two of whom died during the legal process, but the suit did not succeed. In 2015, legislation in Connecticut creating an aid-in-dying law failed to make it out of committee.

What’s clear is that more and more lawmakers throughout the country will be tackling complex questions about quality of life and when a life is really over. Even supporters of physician assisted suicide acknowledge that giving patients the option of terminating their lives isn’t an easy concept to accept. “It’s fraught with moral unknowns,” DeWolf admits. “Is every moment of every life valuable? Who gets to choose when life begins and ends?”

*CORRECTIONS: A previous version of this story wrongly stated that the American Medical Association adopted a neutral stance on aid-in-dying in 2016. While the AMA at-large has not changed its position, some of its state chapters have. Additionally, because of changes made during the editing process, this story originally included multiple references to "euthanasia." In fact, euthanasia is not equivalent to physician-assisted suicide, and the words should not have been used interchangeably.