Each annual budget crisis and round of layoffs had begun to wear him out, he said. Then, talks of pension reform in the state legislature escalated last year, and some of his colleagues decided it was time to leave. Not knowing how the eventual reforms would play out was enough to help convince Mueller, 52, to move up his retirement date to December 31. “There was some uncertainty about what’s coming next,” said Mueller, who plans to work as a contractor for a law enforcement training firm. “It was just the last little nudge that I needed.”

More than 9,500 Oregon state employees called it quits last year – a 44 percent increase from 2012 – as they opted to begin drawing checks from the Oregon Public Employee Retirement System (OPERS). Similar scenarios played out elsewhere in recent years as debate over pension reform in state legislatures sparked a corresponding spike in public employee retirements.

A Governing review of data provided by a sample of retirement systems found that recent pension reforms contributed to significantly more workers filing retirement paperwork in at least six states: Georgia, Illinois, New Jersey, Ohio, Oregon and Wisconsin.

Part of the extent to which pension reforms caused public employees to head for the exits hinges on the nature of changes to plans. But in some states, retirements are more driven by the tone of the political rhetoric and cuts put on the table.

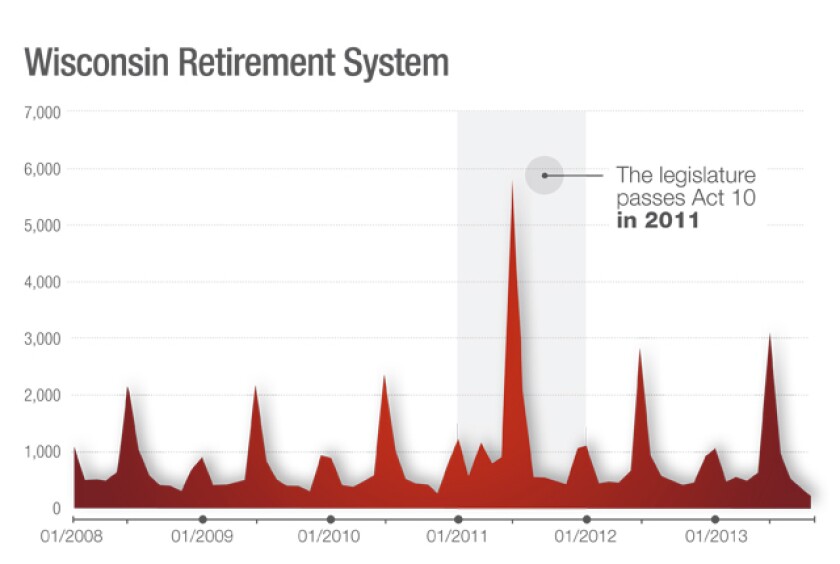

When Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker pushed through controversial changes to collective bargaining and pensions in 2011, retirements nearly doubled. The Illinois State Employees Retirement similarly registered a 47 percent year-over-year surge in 2012 when debate in the legislature began to ramp up. In some other states, reforms had no noticeable effect.

The state legislature also passed its own changes, including reducing cost-of-living-adjustments for OPERS retirees. Although the bill does not yet affect active employees, many still opted to leave. “It’s more of an emotional response to what some people see as a continuing disrespect of public employees,” said Greg Hartman, an attorney representing Oregon’s public employee unions.

OPERS reports that every year the legislature takes up the issue, it prompts a corresponding uptick in retirements.

Legislation in recent years brought drastic reforms in some states, but only minor adjustments in others. In 2012, 10 states overhauled systems with structural changes, such as replacing defined-benefit plans with hybrid or defined-contribution plans. Some states further raised employee contribution rates and cut benefits or cost-of-living-adjustments. Others raised the retirement age.

The majority of states examined that enacted pension reforms did not record notable upticks in retirements, including Montana and New Mexico, which both passed legislation in 2013.

Governing surveyed readers in November and December to gauge the effects of pension reforms. Of the limited number of senior state and local officials who reported pension adjustments were implemented, 46 percent said they caused employees to consider retirement or look for new employment.

By and large, most reforms alter benefits or contribution rates for current employees regardless of when they retire, or make changes for newly-hired workers. But it is clear that when lawmakers or pension boards set cutoff dates for current employees, retirements subsequently spike. The Employees’ Retirement System of Georgia, for example, eliminated a tax offset that meant a cut for members retiring after last June. According to state data, 2,060 members retired in the first half of the year before the change, a 52 percent increase from the same period in 2012.

Members of the State Teachers Retirements System of Ohio similarly avoided a five-year cost-of-living benefit adjustment freeze by retiring before August, instead incurring just a one-year freeze. The system reported a small increase in retirements last fiscal year, which spokesman Nick Treneff attributed to the state reforms passed in 2012 along with improving stock portfolios. The Ohio Public Employees Retirement System also reported that it recorded an increase in late 2012.

It’s often not so much the reforms actually implemented that push employees to retire as it is the threat of benefit cuts that arise during political debate. Perhaps nowhere was this more evident than Wisconsin, which saw a sharp spike in retirements as public employees occupied the state Capitol to protest the Republican-backed 2011 Act 10 reform bill, which included changes to pensions. “It was all driven by the politics and what employees were seeing and hearing from the capitol,” said Marty Beil, executive director of the Wisconsin State Employees Union.

Matt Stohr, an administrator with the Wisconsin Department of Employee Trust Funds, reported call volume nearly doubled after the legislation was introduced. By the end of the year, about 15,600 workers – or 6 percent of active employees – had retired, compared to between 8,000 and 9,000 in a typical year.

Those retiring in 2011 did not gain any pension benefits by not staying on state payrolls. Some of them, like Bob McLinn, who worked 27 years as a state corrections officer, say they accelerated their retirement because of Madison politics. “It pushed me over the edge,” McLinn said. “I wanted to protect [my pension] from any takeaways that were being discussed at the time.”

A similar story played out in Illinois, where debate in the legislature on how to tackle the state’s dire pension woes began heating up in 2012. “Discussions around the legislature in pension reform were a driver for a lot of employees to make this decision to retire,” said Ben Winick director of policy and administration for the state Office of Management and Budget. About 4,700 State Retirement System of Illinois members retired that year; there were 3,200 retirements in 2011 and less than 3,000 in 2013.

Retirements among state employeesdipped last year, which Winick attributes to a better understanding of reforms as talks progressed and the fact that many had already left in 2012.

The only financial incentive for current employees to retire is for Tier 1 workers age 50 and over, who can avoid seeing their cost-of-living adjustments skipped for one year by retiring before July 1. Tim Blair, executive director of the State Retirement System of Illinois, said he suspects some of those leaving may feel their pensions have more solid legal protections if they’re retired.

It’s too early to say whether the reforms could push more employees to head for the exits over the next few months, but Blair expects to know soon. “It could be a really busy spring for us,” he said.

The New Jersey Public Employees Retirement System (PERS) similarly saw retirements jump by about 3,000 in 2010 and 2011. Chris Santarelli, a spokesman for the Treasury Department, reports public discussion surrounding pension and health benefit changes eventually enacted in June 2011 may have played a role. The past two years, between 8,000 and 9,000 PERS members filed for retirement.

In New Jersey and other states, pension reforms occurred on top of demographic shifts that are already exerting pressure on retirement rates. Many systems project higher levels of retirements for years to come as baby boomers set to exit the workforce. In Oregon, for example, a third of the state employees who participate in OPERS are eligible to retire.

Many boomers delayed retirement during the recession. When they heard talk of tinkering with their pensions, it’s likely that many decided it was time to not put it off any longer.

Retirement System Data

Governing obtained current and historical retirement data from a sample of 15 states implementing adjustments to pensions in recent years. An analysis of data and interviews with state officials indicated pensions reforms contributed to significantly more retirements in the following states reviewed: Georgia, Illinois, New Jersey, Ohio, Oregon and Wisconsin.

The following charts illustrate spikes in employee retirements for systems with available monthly data. Please note that most systems typically experience regular increases near the end of fiscal or school years.