Divided by Design, a report by Smart Growth America, documents how our transportation systems have harmed and continue to harm low-income communities and communities of color. Yes, by design. In addition to dividing neighborhoods along class and racial lines, the build-out of interstates and other broad, multilane roads in urban areas is responsible for minorities forfeiting a huge amount of equity from homes that were taken from them to make way for the roads. Local governments also lost hundreds of millions of dollars in tax revenues because businesses were shuttered and real estate was removed from their tax rolls.

Public officials are mostly indifferent to this past, but they can and must work to ameliorate this tragic history.

First, they must acknowledge and understand the scope and lingering effects of the problem. While the Smart Growth study documents the impact nationwide, it focuses particular attention on Atlanta and Washington, D.C., as two examples of its worst effects. “The displacement, destruction and resulting barriers entrenched many disparities and inequalities seen in the city today,” the report concludes, in reference to D.C. There and elsewhere, interstate highways made it easier for whites to migrate to the suburbs at a time cities were becoming more diverse — the phenomenon referred to as “white flight.”

The most disturbing aspect of all of this was that the disruption and destruction to Black neighborhoods were done deliberately. “They took tax money from the cities where nearly 90 percent of GDP and tax revenues were generated and built highways to new suburbs with racial covenants, and did it in ways to further isolate communities that had already been starved of capital because of the Housing Act of 1934,” Carlton Brown, CEO of Direct Invest Development, a New York-based minority-owned impact development firm, told me. Richard Rothstein, whose books focus on the history of segregation, called the federal housing programs begun under the New Deal a “state-sponsored system of segregation.”

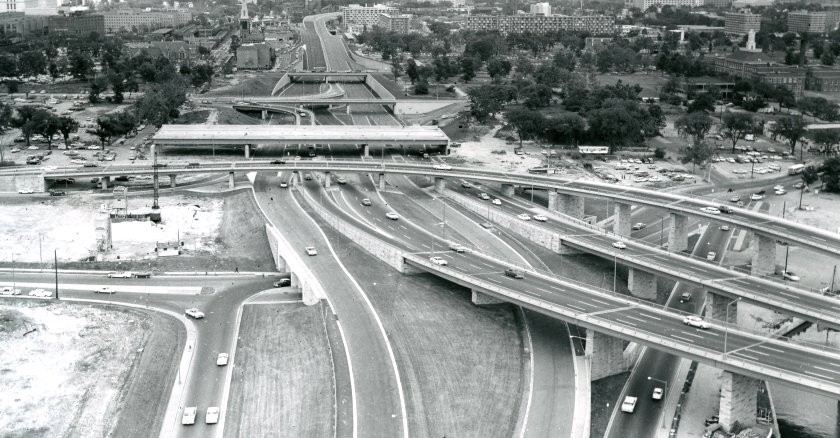

The Smart Growth study estimates that the nation’s interstates displaced 475,000 households and over a million people in less than two decades. In D.C. alone, the building of Interstates 395 and 695 consumed more than 400 acres and displaced 23,500 people, most of them African Americans. It resulted in 1,400 housing units being destroyed, wiping out $483,000 in what would be average home equity if those homes existed today. The city lost the ability to tax approximately $1.4 billion in home value, costing it at least $7.6 million in property taxes per year.

Similarly, the construction of I-20 ripped through the heart of Atlanta, displacing at least 7,500 people and destroying an estimated 2,200 homes, most of them owned by Black residents. That destruction wiped out $596,000 in average home equity if those homes existed today. The city lost the ability to tax at least $676 million in home value, costing it at least $6.4 million in property taxes each year. The highway’s intensification of segregation is undeniable: Longtime Mayor William Hartsfield referred to I-20 as the “boundary between the white and Negro communities.”

What was lost in Atlanta? This animation, using historic satellite imagery, visualizes the path of I-20 before and after construction. (Smart Growth America, produced in partnership with @Segregation by Design)

Deliberately running the highways through the heart of Black and brown communities to enforce racial segregation was merely par for the course at the time. As the Urban History Association has documented, in the 1950s Alabama Highway Department Director Sam Engelhardt, who was also the leader of the Alabama White Citizens' Council, personally intervened to route I-65 through prosperous Black neighborhoods in West Montgomery, which included targeting the home of civil rights leader Ralph David Abernathy for destruction.

Of course, the nation’s system of nearly 47,000 miles of interstate highways has had positive benefits, supporting commerce and providing Americans with enormous mobility. Moreover, it is not practical to demolish them all. So what can and should be done? First and foremost, because of the roads’ role in furthering the racial segregation of neighborhoods, public officials must be intentional about reversing this sad history and reconnecting their cities.

One way to accomplish this is by building linear parks under the highways or on bridges above them. That might happen even in Sam Engelhardt’s Alabama: The city of Birmingham has studied building a linear park underneath I-20 and I-59. Los Angeles is considering creating a 128-acre linear park and multimodal corridor with 4,000 units of affordable housing on top of the Marina Freeway. Other cities are working with architects and urban designers to reimagine ways to rebuild and reconnect communities by building linear parks.

Another idea cities should explore, utilizing data from the Smart Growth report, is to commission studies to determine how much is owed to residents who were victimized by racist transportation decisions. Those residents or their descendants should be entitled to some form of recompense; had many of them been able to hold on to their homes, in some cases their families would be a half-million-dollars wealthier today. Cities that were complicit in promulgating policies that led to the taking of land from people of color must do more than simply say they are sorry.

Finally, state and local governments must discontinue pouring billions of dollars into the construction of roads that not only worsen racial segregation but also damage our environment by contributing to flooding, enlarging the carbon footprint and adding to noise and pollution. The public must become less reliant upon automobiles: It is time to invest in new technologies that make transit more affordable, available and safe, and to stop fighting the building of complete streets where motorists share roads safely with bikers, joggers and pedestrians.

Government at all levels got us into this mess by building transportation infrastructure in a way that has separated us from each other. Fixing the problem will be worth the cost.

Governing’s opinion columns reflect the views of their authors and not necessarily those of Governing’s editors or management.

Related Articles