Caro documents the misdeeds of an unelected but long-unstoppable “master builder” in detailed and depressing, but utterly convincing, fashion. Moses needlessly destroyed the functional and close-knit community of East Tremont in the South Bronx to build the monstrous Cross Bronx Expressway. He refused to make room for transit projects, subjecting his city to the automobile traffic gridlock that still prevails. He pushed through high-rise housing projects that quickly deteriorated into dangerous and decrepit monstrosities. He usually got what he wanted, but not always, as when he sought to ram a highway through Washington Square in Greenwich Village and three more that would have torn through the streets and neighborhoods of Lower and Midtown Manhattan.

Caro gives Moses credit for the parks and recreational facilities he created early in his career, but all in all he portrays Moses as a willful dictator, and readers have little reason to challenge that judgment. There is no need to go into more detail at this point. The facts are there for any reader to discover.

But thinking about The Power Broker now, decades after first coming across it, I find myself unexpectedly feeling that something is missing. Not inaccurate, or even misleading, but simply absent. That is the knowledge that the kinds of disasters Moses created weren’t unique to New York during much of his time in power. They were happening, to a greater or lesser extent, all over the country.

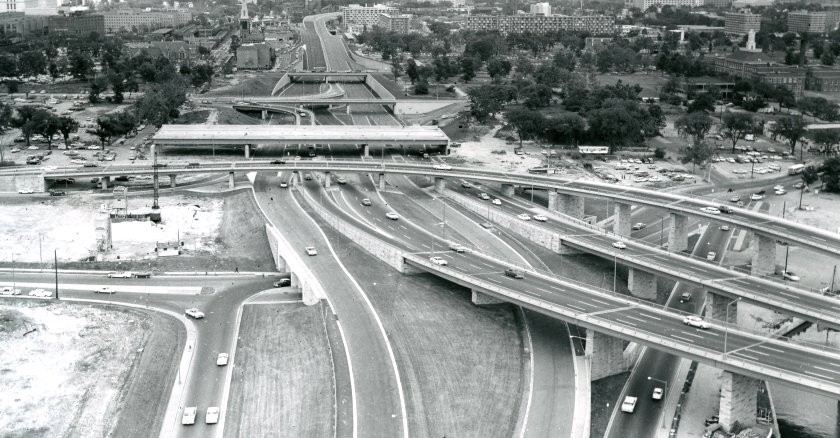

Pick any large city in the 1950s, when many of Moses’ worst visions were being realized, and you will find neighborhoods being bulldozed, hideous highways being constructed and barely livable housing projects being built. Moses-style misdeeds weren’t just a New York phenomenon — they were a fact of life in postwar urban America.

A few examples should make the point. In civilized St. Paul, Minn., the vibrant black neighborhood called Rondo was leveled by the construction of Interstate 94 in the late 1950s. The record shows that 700 homes were destroyed and 300 businesses forced to close. This was every bit as arrogant as what Moses did in East Tremont.

In New Orleans, the historic and lively 7th Ward and surrounding Tremé community were demolished to make way for the construction of Interstate 10 through the city. Claiborne Avenue lost precious old oak trees and 500 homes. As in the rest of the country, the federal government, not the local leadership, paid most of the bills.

Moses built plenty of dysfunctional public housing in New York in the 1950s, but it was no worse than — perhaps not as bad as — high-rise projects like Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis and the Robert Taylor Homes in Chicago, which have been long since obliterated. These buildings, and many of the highways built around the same time, were made possible by the 1949 federal housing law, which allowed cities to declare neighborhoods “blighted” or “slums” and apply for more than $1 billion in federal loans to destroy property and replace it with new construction under the label of urban renewal. All of this would have happened throughout urban America had there never been a Robert Moses.

NONE OF THIS CONDONES Moses’ massive and misguided efforts to remake New York according to his vision. But it makes a larger point not only about city planning but about our attitude toward public issues of all sorts. We assume they are local when they are actually societal.

But the fallacy of localizing broader trends goes well beyond the issues of urban planning. City leaders have agonized for decades over the poor performance of their inner-city schools, and have tried everything from mayoral control to neighborhood empowerment to fierce school-by-school competition. None of the school reform schemes have accomplished much. The most important reason is that school performance largely tracks demographics, not educational strategy. If you know the population characteristics of a school system, you can tell pretty accurately which schools are going to come out well. I don’t offer this as a criticism of any population cohort or any group. It is just societal reality.

In 2002, the sociologist Eric Klinenberg, a Chicago-based academic, published Heat Wave, a shocking and well-researched book documenting more than 700 deaths that occurred in the city during a period in July of 1995 when the heat index rose into the 120s. I don’t dispute any of Klinenberg’s evidence, but I’ve always found it demographically incomplete. Slum conditions were as bad in Baltimore, Cleveland, St. Louis and a host of other inner cities as they were in Chicago. It defies logic to believe that similar tragedies weren’t occurring there. The reason we failed to hear about them is that no one did the conscientious research that Klinenberg did.

BEHAVIORAL SCIENTISTS TALK about a cognitive syndrome they call availability bias. It means that we tend to attribute events to causes that are evident right around us, ignoring equally plausible evidence that happens to be further outside our reach. It may seem an obvious point, but it is one we usually miss. Mayors of a generation ago saw families departing for the suburbs and assumed they were making mistakes. The larger truth is that they were falling into the trap of availability bias.

We’ve drifted a bit far from the case of Robert Moses. Nothing I’ve written is meant to excuse any of Moses’ misdeeds or to disparage the achievement that The Power Broker was and is. It’s simply meant as a caution that when we try to explain important public situations and events, especially negative ones, we need to look somewhat further than we are in the habit of doing.

In any case, the most broadly absorbed lesson of Moses’ career has not been so much the substance of what he did but the unchecked power he was able to accumulate without ever serving in elective office. At least that is the lesson that other cities and governments seem to have absorbed. Wariness of unchecked authority has led cities all over the country to place obstacles in the way of planning projects that can make it difficult for even the most well-meaning developers to build anything anywhere within the city limits. This syndrome is documented incisively in a forthcoming book by Marc J. Dunkelman, Why Nothing Works. “The determination to protect against latter-day Robert Moses-types now serves not only to thwart abuse,” Dunkelman writes, “but also to undermine government’s ability to do big things.”

Perhaps it is ironic that the weakening of government authority is the one consequence of Caro’s masterpiece that transcends its localism. When we solve this problem, we will not do it in one city. We will do it in many places at once. That is the way these things work.