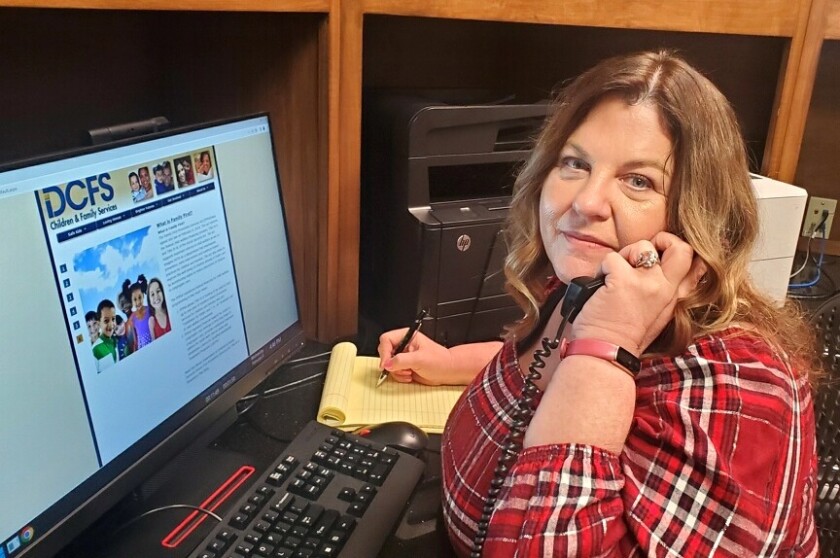

It’s not a matter of money; the DCFS budget is the best Malnar’s ever seen. As is the case for many in the public sector, her department is suffering the effects of a lingering inability to rebuild a pandemic-depleted workforce. For those in frontline jobs, the stresses and risks can be especially great.

Malnar and her staff have to be available 24/7, and they can’t control the volume of requests for help. “We can’t waitlist a hurting child, but if an investigator’s run ragged and doesn’t have time to go home and sleep, you wonder about their ability to assess child safety.”

The quality of local government services can have a big impact on the lives of citizens. The sector has been especially slow to rebound from pandemic losses.

Council 31 of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), representing more than 90,000 current and retired public service workers in Illinois, conducted a survey of members from departments such as corrections, juvenile services and veterans affairs who work in facilities that operate around the clock.

The shortages Illinois is facing reflect trends across the nation, says Dalia Thornton, director of research and collective bargaining for AFSCME. She cites a report from NeoGov which found that the number of applicants per open public-sector job decreased by 70 percent between 2019 and 2022.

The public sector is short over 500,000 jobs, says AFSCME President Lee Saunders. To help turn the tide, his union is launching a retention, recruitment and outreach campaign for public service workers, “Staff the Front Lines.”

“We’ve got to be creative,” Saunders says. “States and cities across the country are working on this issue and we’re hopeful that we can work together.”

(AFSCME)

Unions and Retention

Crosby Smith is a care provider at Ludeman Developmental Center, a residential facility for individuals with severe and profound developmental disabilities, and president of AFSCME Local 2645. He’s worked for the state for 21 years, and over time has seen the impact of declining staff resources on care.

The standard for some residents at Ludeman is one-to-one supervision, he says, but recently circumstances have arisen where as few as three staff will be responsible for as many as 10 individuals, some in groups and some needing one-to-one attention. At times, certified nursing assistants have been brought in on a temporary basis to fill gaps, but this disrupts the continuity of care that has been found to have significant benefits for those with severe disabilities.

“There’s not really normalization [a normal rhythm of the day] until you stabilize the staff,” Smith says. “You can see the mood change, and for those of us who’ve been dedicated to this work, that’s disheartening.”

Even at the best of times, Malnar’s staff can face serious pushback against their efforts to do good. “When we go out in the field and say, ‘I'm from DCFS,’ it's not a lovely home visit,” she says. “We get called names, we're treated terribly.” Two workers have been murdered in the last five years.

Both Malnar and Smith have observed that it’s rare for staff to be praised for good work, but common for them to be upbraided if things go wrong. Surveys of public-sector employee satisfaction have consistently found acknowledgment, encouragement and respect to be among the top things employers could do to reduce employee stress.

Malnar recalls receiving a pin in the mail recognizing 25 years of service that came with no written acknowledgment. “It was almost more of a slap in the face than an award. Really, you couldn’t have put a note in there or had a manager hand carry it to my office?”

As union leaders, Smith and Malnar consider it part of their duty to provide emotional support to members when needed. This is a benefit of community that goes beyond pushing for better wages and working conditions, one that may not be widely recognized as a factor in retention.

Smith hopes the public can come to understand that union membership is not just a matter of self-interest. “We need for people to know how dedicated we are and how much, each day, we advocate for things to be better,” he says. “The people that do this care about their jobs.”

(AFSCME)

Job Fairs, Faster Hires

Public education is the first step to helping understand the importance of frontline, public-sector work, Saunders says. This includes reaching out to high schools and community colleges.

Job fairs are another piece of the strategy. A recent job fair organized by District Council 37, in cooperation with the New York City Department of Citywide Administrative Services, attracted hundreds of job seekers.

Streamlining hiring also is a priority. Malnar says it can take “at least nine months” for her to get a replacement for an investigator who leaves the job. When that time lag is added to the months involved in training and gradually increasing case load, two years can pass before the employee who left is truly replaced.

This is unforgivable, she says. “All that time, the other workers are suffering and, possibly, the children we serve are suffering — no matter how big our hearts are, we can only do so much.”

Saunders has heard stories of hiring processes that can take as long as a year. “Who in the world would wait a year when they are looking for a job?”

Apprenticeships will be extremely important to moving things forward, he says. With support from Oregon Rep. Suzanne Bonamici, AFSCME recently secured $900,000 in federal support for pre-apprenticeship education and training that would help 60 individuals pursue careers in behavioral health and another 60 to become certified drug and alcohol counselors.

A Real Problem

In the early stages, AFSCME will focus its work in places where it has strong relationships with governors, mayors or city councils, says Thornton. Jurisdictions that have been anti-union or opposed collective bargaining may be less likely to embrace a union as a stakeholder in their personnel problems, a perspective that could change over time.

(AFSCME)

Government already has the highest percentage of union members of any sector, almost 30 percent in state government and more than 40 percent at the local level. Many of the policy reforms AFSCME hopes to see would benefit workers whether they are union members are not.

The administrative challenges coming with the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE) are significant. In some states, an insufficient number of personnel to manage SNAP (food stamp) benefits has already created crisis situations, with citizens waiting months for assistance they depend on to buy food.

“Our affiliate in Alaska recently asked us for workplace violence training because people were so hungry and angry that they hadn't gotten their benefits that month they were attacking the members who were trying to do their work,” says Thornton. The burden on these workers will be exacerbated by the fact that SNAP benefits will decrease in coming months as emergency allotments end.

The end of the PHE also means the end of enhanced federal support for Medicaid and the end of continuous enrollment. Redetermination of eligibility and enrollment will bring huge workloads in 2023, and as many as 14 million Americans could lose coverage, with a ripple effect of administrative disruption (and added costs).

These additional needs, aftereffects of efforts to contain the impact of COVID-19, come on the heels of pandemic-caused worker shortages that are affecting everything from the response times of 911 dispatchers to the safety of workers in correctional facilities.

“This is a real issue and a real problem, not just for our union and for those who provide public services,” says Saunders. "It’s a real problem for the citizens who rely upon public services every single day.”

Related Articles