According to the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), local governments spend $20 billion a year in capital expenditures on sewers, and $30 billion a year operating and maintaining them. In 2016, a U.S. EPA survey determined that $271 billion was needed to improve and maintain the vast wastewater infrastructure, most of it within five years.

Wastewater may not be front of mind in most discussions of green jobs, but this sector offers opportunities to make profound contributions to sustainability and environmental health. Preventing dangerous pollutants from contaminating watersheds and the ocean and damaging the web of life has elemental importance. But it’s not the only “green” service that workers in this sector provide.

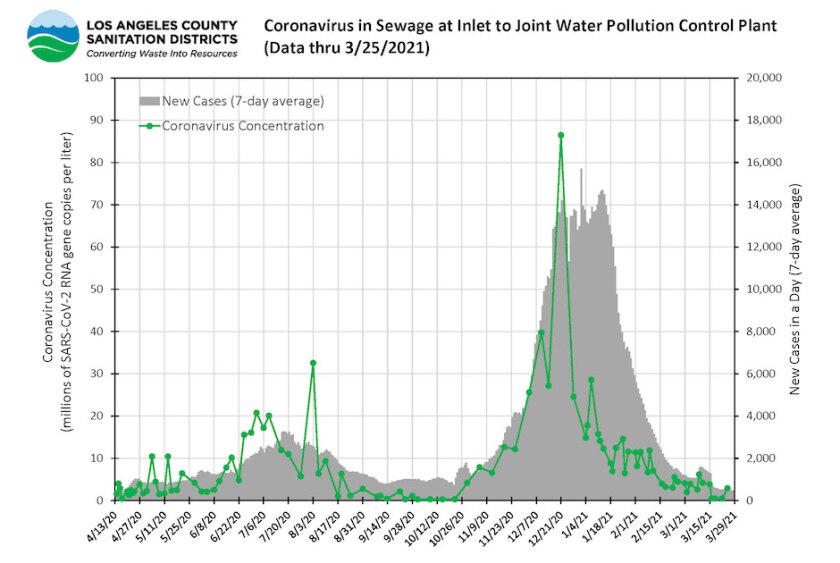

Managing wastewater, including storm water, is also a front-line public health service. It is essential to mitigating the water-borne spread of pathogens that account for 80 percent of illness and death in the developing world. As part of the global response to COVID-19, scientists have expanded efforts to measure the presence of viruses and bacteria in sewer water to help predict and control the spread of infectious diseases.

Water jobs pay more, on average, when compared to all occupations in the U.S., and they pay up to 50 percent more to workers at the low end of the income scale. But despite the combination of high purpose and solid pay, wastewater agencies across the country face worker shortages.

Hidden from View

The fact that wastewater jobs are largely hidden from view is not surprising, according to Steven Harrison, senior manager of operator programs at the Water Environment Foundation (WEF), an international not-for-profit technical and educational organization for water quality professionals.Sewage treatment plants are typically outside of town at the end of dirt roads, pipes are underground and hundreds of millions of dollars are spent each year on odor control. “For a long time, the industry went to a great deal of effort to make itself invisible and sadly, it has succeeded,” he says.

Harrison sees these jobs as the most crucial in any community, essential to all commerce and all life. The readers of the British Medical Journal voted clean water and sewage disposal as the greatest medical advance in a century in a half, he says. “These are not mundane public works jobs.”

The current demographics of the workforce make shortages inevitable. The average age of respondents to a 2016 independent survey of water and wastewater workers was 56; almost 40 percent were 60 or older. Two-thirds are white, another missed opportunity for growing the pool of prospects.

Between 30 and 50 percent of current employees will be eligible to retire within the next five to 10 years. For a time, it seemed that the economic turndown of 2008 might delay an impending gray tsunami, says Chad Weikel, education and workforce manager for the American Water Works Association (AWWA). “I think we’re there now — we’re hearing anecdotal things and seeing good data that show we've got a lot of folks retiring, and we don't have enough in the pipeline to replace them.”

In California alone, there are an estimated 6,000 water job openings each year, according to the California Water Environment Association (CWEA), a nonprofit that provides education, certification and advocacy services to wastewater professionals in the state. Qualifications for entry range from GED to PhD, says Alec Mackie, CWEA’s director of communications and marketing.

These green jobs don’t depend on legislative subsidy, according to Harrison. They pay enough to sustain a family and cannot be outsourced. “They’re largely immune to economic externalities, and they’re necessary wherever people live,” he says. “Who wouldn’t want a job like that?”

Technology is constantly evolving, regulations tightening and the challenges posed by storms and drought becoming more and more intense. The wastewater industry depends on continuous learning, and it covers the costs. “The utilities will train the heck out of you once you get in the door,” says Mackie. “This is the sector where your dig your way to the top.”

California has an outsized need for professionals with the skills to stay ahead of climate change, increased demand and some of the nation’s strictest water regulations. Utilities, nonprofits and educators in the state are finding innovative ways to attract workers.

A Regional Approach

With wastewater workers retiring in droves, the chances are slim that a father, uncle or neighbor might point a young person toward a water job. In response, BAYWORK, an association of Northern California water and wastewater utilities, developed a collaborative approach to workforce development that is unique in the U.S. Established in 2009, it has grown from four charter members to a consortium of 43 agencies. Members pay dues according to their number of employees, which can range from a handful to 2,500.Most water agencies are not large; nationally, 85 percent have three or fewer employees. Smaller utilities don’t have capacity for workforce development, which is one of the reasons BAYWORK was created, according to its president, Catherine Curtis, the workforce reliability manager for the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC). “They may have one human resource person for the whole company, and that person focuses on the insurance and benefits and not so much on candidate development,” she says.

Members have access to BAYWORK’s research and training events, developed “by utilities, for utilities,” adds Curtis. A “workshops on wheels” series, conducted virtually during the pandemic, takes staff from district to district for presentations on innovative approaches to shared problems.

Utility workers are actors in this video from “Tiny Bubbles,” a BAYWORK lesson plan that shows students how to use algebraic equations to calculate the rate at which oxygen and microorganisms should be added to wastewater to rid it of contaminants.

BAYWORK's website includes career profiles, video interviews with workers, outlines of required training, and links to educational and apprenticeship programs and employers. Live events have been on hold during the past year, but the association has continued to provide them online, from webinars on women and veterans in water to educator workshops.

Curtis volunteers her time, as do others leading the consortium’s work. “Our mission is to protect public health and the environment — how can you do better than that?,” she says. “It’s in such alignment with my personal goals that every day is a joy.”

BAYWORK could and should be replicated throughout the country, says the WEF’s Harrison. “We’re trying to replicate it right now, here in the Mid-Atlantic.”

Model programs have also sprouted in water-stressed Southern California.

Center for Water Studies

One of the country’s most-respected programs for water and wastewater job training is at the Center for Water Studies at Cuyamaca College in San Diego. It is the flagship for more than 20 such programs at California community colleges.The center draws on work that began in 1960, when the city of San Diego and San Diego junior college partnered to develop training for operators at water and wastewater treatment plants, in response to tightening standards for water quality. The program moved to Cuyamaca in 2003.

“We have all of the same testing equipment that a water treatment plant lab would have,” says Don Jones, a veteran in wastewater treatment and longtime instructor at Cuyamaca College. He has described the center as a “pipe dream come true.”

Students gain hands-on experience at a fully operational, above ground water distribution system that incorporates equipment donated by industry. They can work on pipes, pumps and valves, take things apart, make repairs, transfer water from tank to tank, measure flow and velocity. Coursework in a backflow lab covers the theory and practical skills needed to prevent contaminated water from moving back into potable water supply, and to pass a certification test.

Jones spent 10 years of his career in employee training and development. His real-world familiarity with the skills needed for water jobs comes with awareness of the need for workers. In San Diego, he says, a third of the water workforce will retire or reach retirement within the next three to five years.

First responders are vital to community health and safety, but so is water. “When’s the last time you called for assistance from a police officer or a firefighter?” asks Jones. By contrast, California’s water and wastewater infrastructure receives a billion hits each day from taps, toilets, dishwashers, washing machines, irrigation and more.

Veterans are also likely to have technology experience and working knowledge of modern control systems. “The equipment used in a water treatment plant is essentially the same as in a missile launch control center,” says Jones. “The Point Loma Wastewater Treatment Plant monitors a hundred thousand data points continuously.”

In addition to opening doors to careers in local water agencies, Cuyamaca’s training offers students lateral mobility. California wastewater standards are among the toughest in the nation, and their certification will be respected in virtually every state, says Jones. Local agencies would be happy for them to stay nearby. San Diego plans for a third of its drinking water supply to come from recycled wastewater by 2035.

Robert A. Keeran

Green Factories

CWEA president, Wendy Wert, is a civil engineer at the Sanitation Districts of Los Angeles County, which includes 24 independent special districts and 11 treatment plants that provide wastewater services to L.A. County. The districts use outreach, social media, branding strategies, mentoring programs and even scholarships to keep 1,400 positions filled.“While the nation is saying there aren’t enough jobs, we need qualified candidates,” says Wert. Her utility has developed classroom materials and an interdisciplinary Sewer Science curriculum for high school students in which they make, treat and test synthetic wastewater.

County utilities are going to be investing billions in water reuse projects, says CWEA’s Alec Mackie. “One of the things we talk to students about is that they have the opportunity to be part of some of the biggest things their communities will ever do.”

Los Angeles County has experienced far more COVID-19 deaths than any other in the country. Sewer water can provide data from 5 million people at less than one percent of the cost of testing, and increases or reductions of coronavirus genetic material show up in waste water in advance of rising or falling cases. Building out this data infrastructure is another vital service.

The goal is to turn treatment plants into green factories, says Mackie, recycling water, generating energy and converting wastewater residual into compost. “We’re trying to go in all these directions, and more, without enough people.”